The Portuguese in Sri Lanka - Secrets of a Lost Empire

A History of Architecture, Cuisine, Surnames, Objects & Expressions

The Portuguese in Sri Lanka left behind a legacy that extends far beyond military conquests and colonial rule. From the imposing fortresses that once guarded their strongholds to the surnames carried by generations of Sri Lankans, the influence of the first European settlers on the island remains deeply embedded in its culture. Though their empire faded centuries ago, traces of Portuguese heritage persist in Sri Lanka’s cuisine, language, traditions, and everyday life.

This article delves into the lasting imprint of Portuguese rule, exploring how architecture, food, and even common expressions still echo a forgotten era. By uncovering these historical fragments, we reveal the secrets of a lost empire – one that, despite its fall, continues to shape Sri Lanka in subtle but profound ways.

Sections

The Dawn of a New Era: Portuguese Ambitions and Sri Lanka’s Kingdoms in the 16th Century

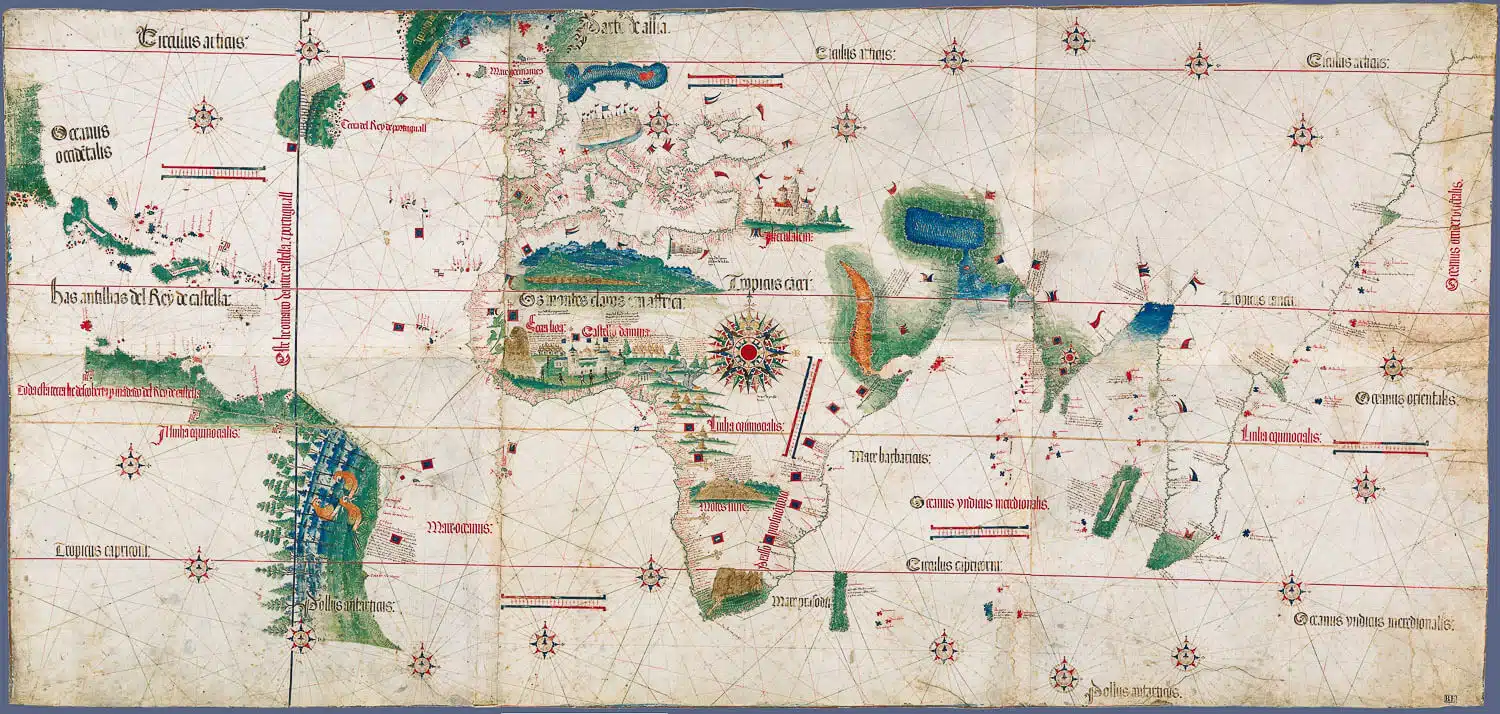

The 16th century was a period of profound transformation, marked by European maritime expansion driven by economic aspirations, technological advancements, and religious fervor. Portugal, a leading naval power, spearheaded this movement, seeking to establish dominance over trade routes and build a vast overseas empire.

Portugal’s Maritime Empire and Expansion in the East

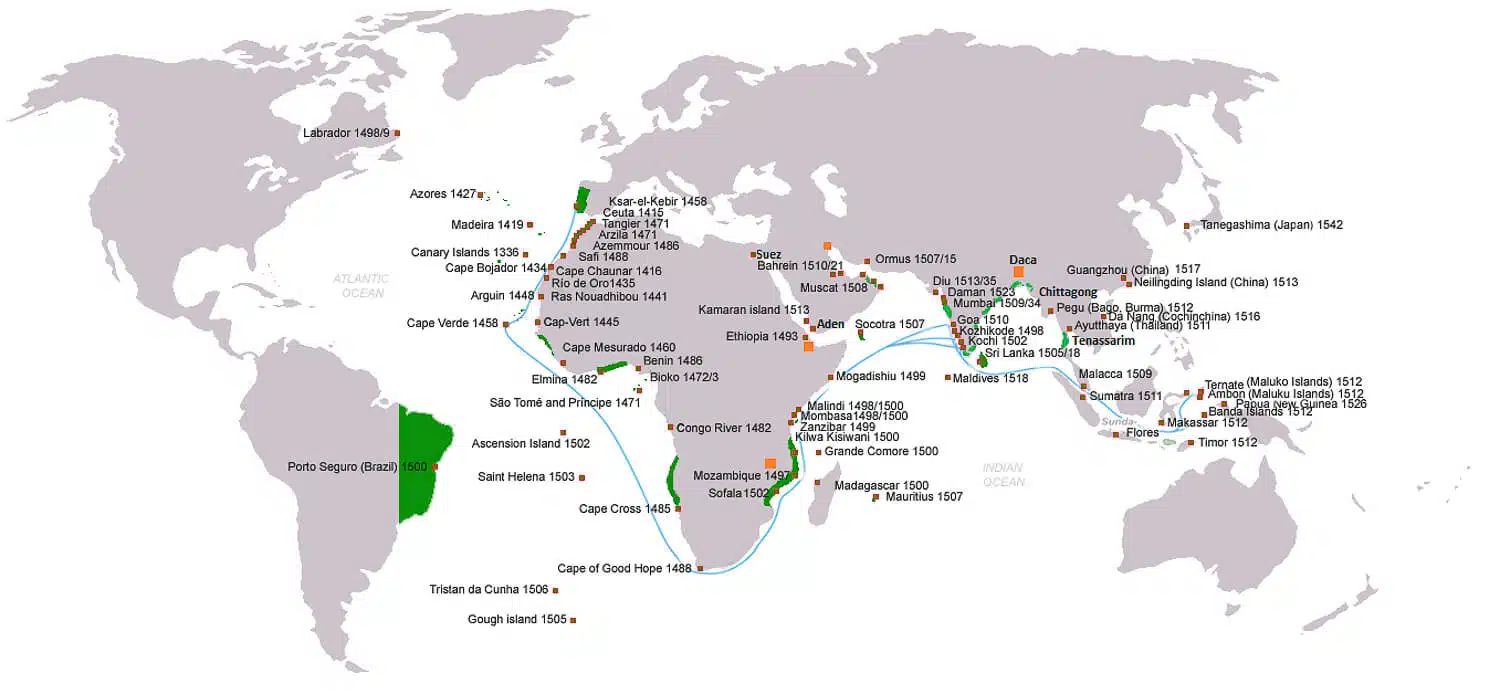

By 1505, when the Portuguese arrived in Sri Lanka, they had already cemented themselves as a formidable naval power in the Indian Ocean and beyond. Under Prince Henry the Navigator and later King Manuel I, Portugal had pioneered maritime exploration along the West African coast in the 15th century, culminating in Vasco da Gama’s historic voyage to India in 1498. This event marked the beginning of Portuguese dominance over the spice trade, which had previously been controlled by Arab and Venetian merchants.

Portugal’s strategic expansion involved capturing key locations to control trade routes and resources. Goa, captured in 1510, became the administrative center of their Eastern empire, facilitating trade and governance. Malacca, conquered in 1511, secured vital trade routes in the Malay Archipelago, connecting the Indian Ocean with the South China Sea. The Portuguese also reached the Moluccas (Spice Islands) between 1512 and 1514, gaining direct access to nutmeg, cloves, and mace, highly sought-after commodities in Europe. Furthermore, they established a strong presence in the Persian Gulf and East Africa, with key outposts in Mozambique, Hormuz, and Socotra, consolidating their maritime power.

The Portuguese expansion was not solely driven by economic motives. The Order of Christ, the successor to the Knights Templar in Portugal, played a significant role in sponsoring explorations with the goal of spreading Christianity. This missionary zeal would later influence the Portuguese approach in Sri Lanka, where they actively sought to convert local populations.

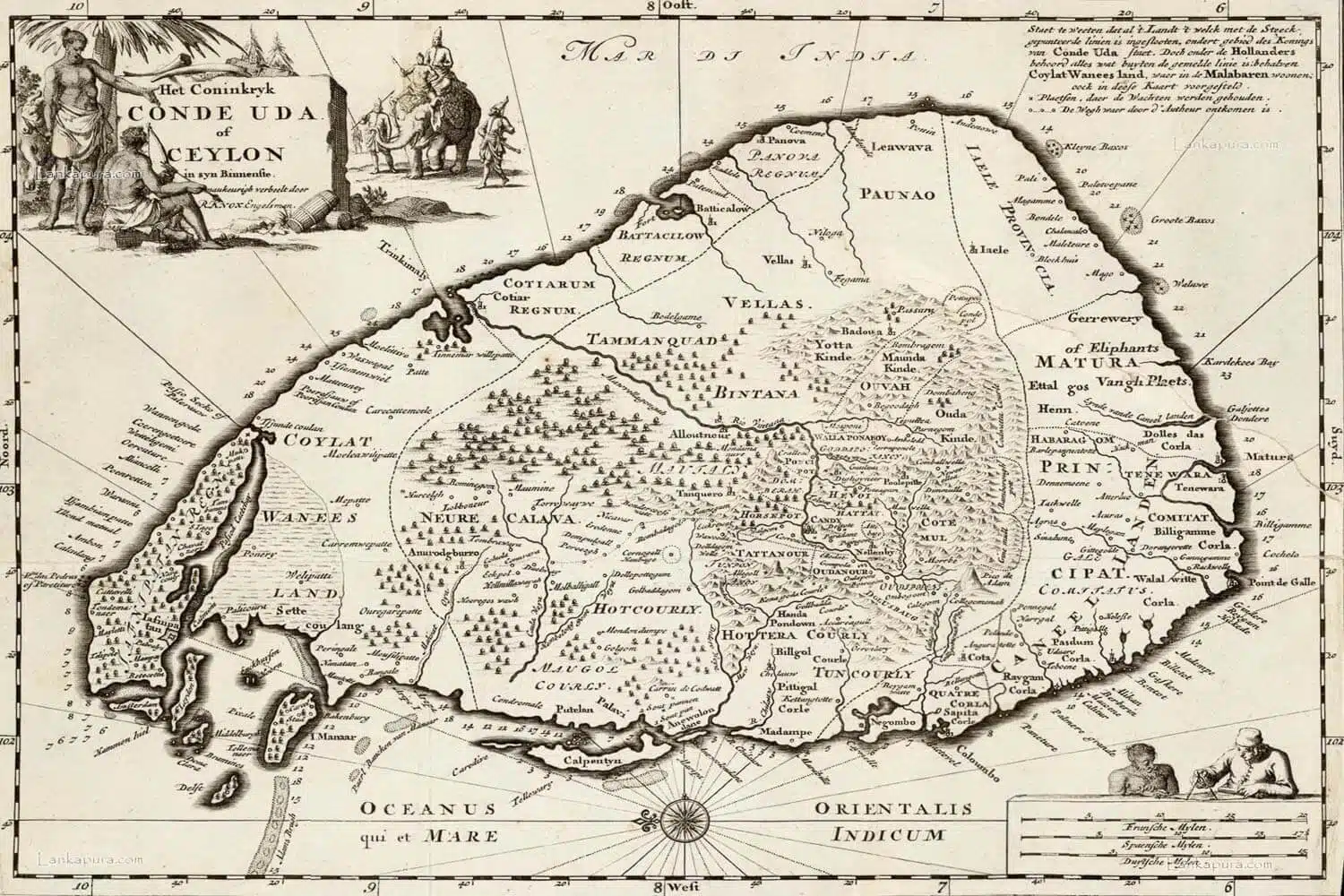

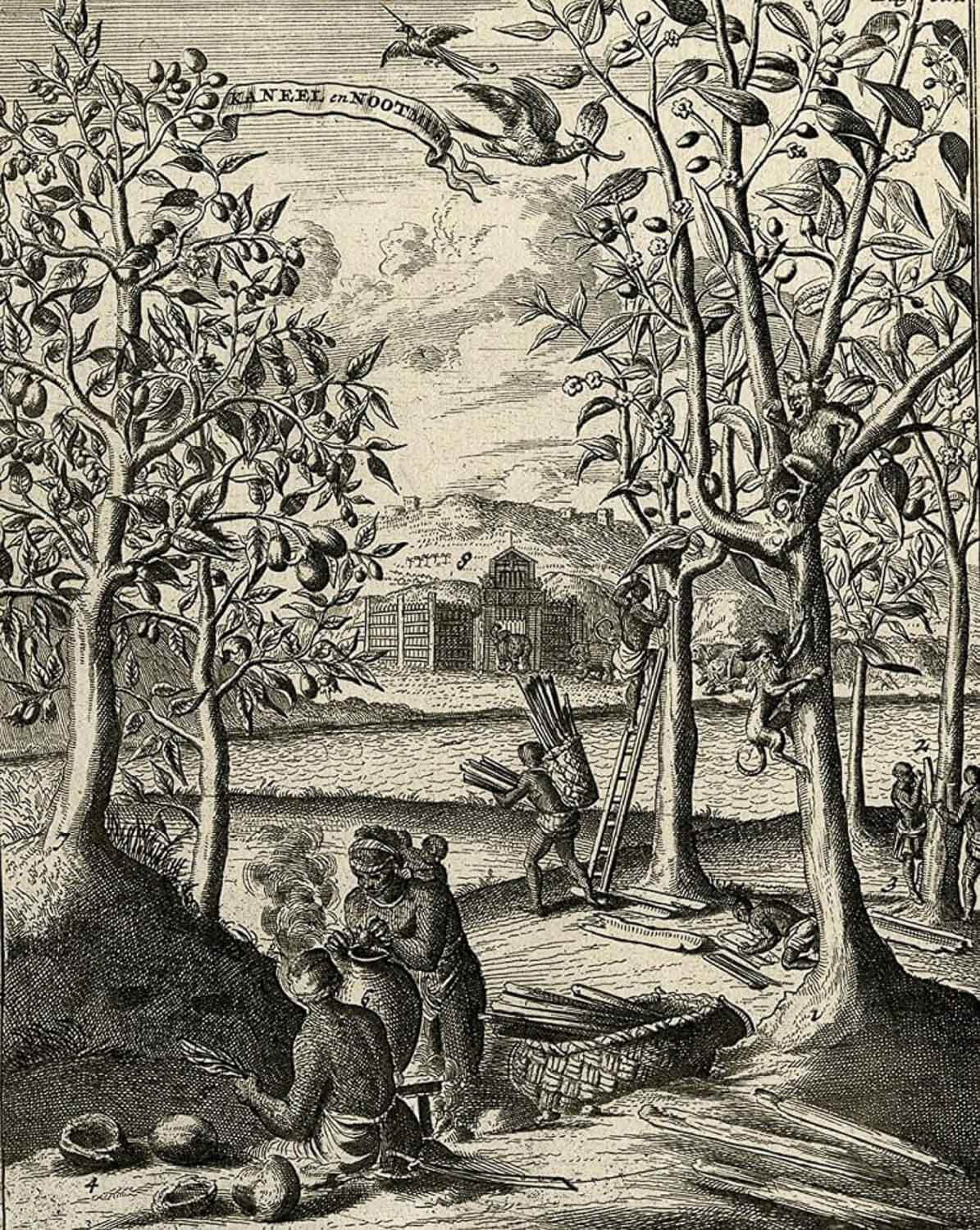

Sri Lanka Before the Portuguese: A Strategic Island in the Indian Ocean

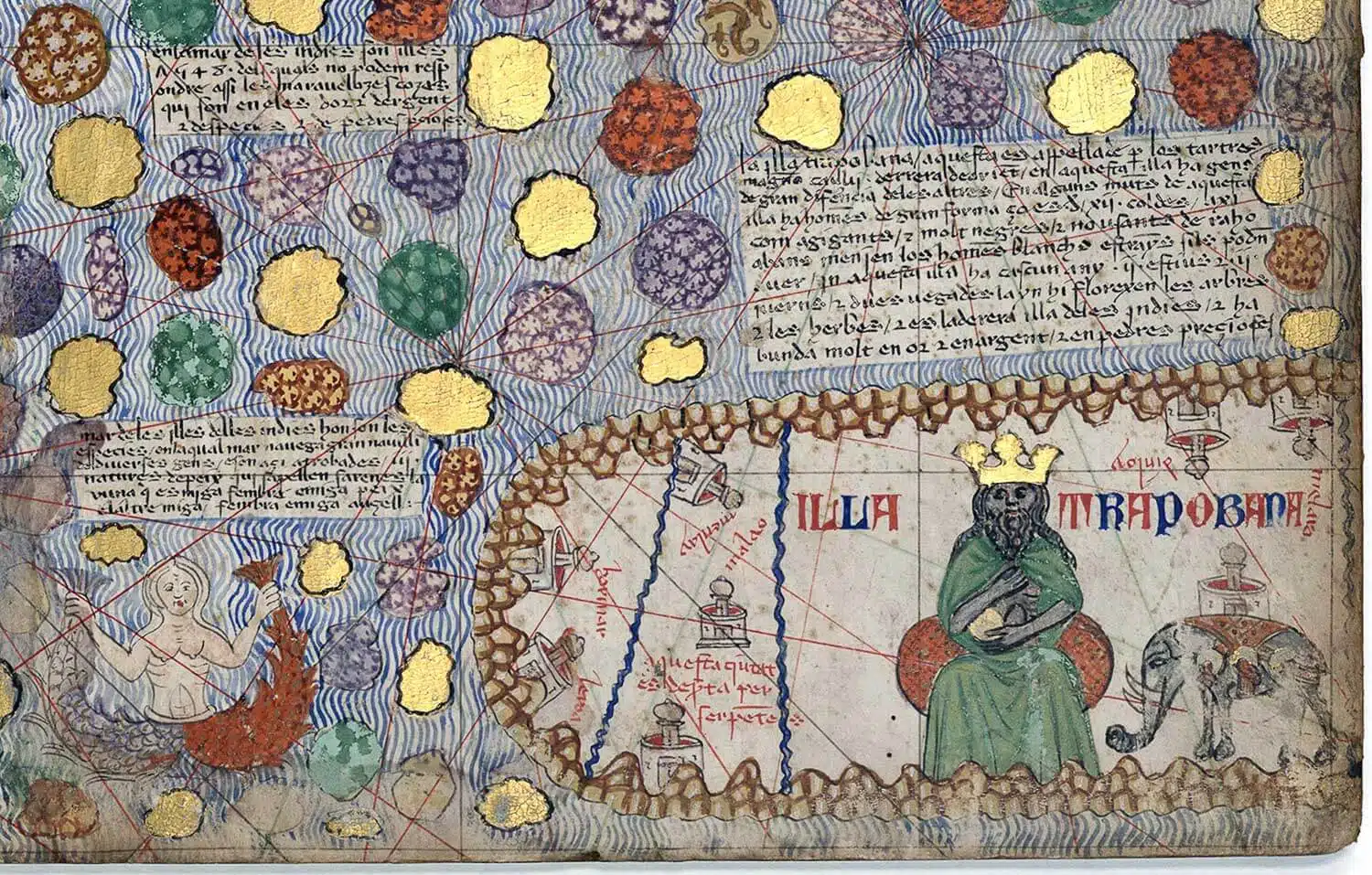

At the dawn of the 16th century, Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon, and earlier referred to as Taprobana by ancient Greek and Roman geographers) was already deeply integrated into the vast trade networks of the Indian Ocean. The island was famous for its high-quality cinnamon, an essential commodity in both Asian and European markets. Alongside spices, Sri Lanka was also renowned for its exquisite gemstones, including sapphires, rubies, and topaz, which traders had highly prized for centuries. This wealth of natural resources placed Sri Lanka in a crucial position within the global trade routes, attracting merchants from India, the Middle East, and even China long before the arrival of Europeans.

For centuries, Sri Lanka had maintained trade relations with:

- South India (Tamil Nadu and Kerala): Tamil and Malayali traders from the powerful Vijayanagara Empire and smaller South Indian polities exchanged goods, ideas, and even political influences. The Arya Chakravarti dynasty of Jaffna had long-standing ties with South Indian kingdoms.

- Arab and Persian Merchants: Muslim traders, particularly from the Middle East, had dominated the spice and gem trade in Sri Lanka for centuries, establishing commercial settlements along the western and southern coasts.

- Chinese Voyagers: During the 15th century, the famous Ming Dynasty admiral Zheng He led multiple expeditions to Sri Lanka, reflecting China’s interest in controlling the maritime silk routes. Some Sri Lankan rulers even paid tribute to the Chinese emperor in exchange for military and economic benefits.

- Malay and Javanese Traders: The influence of Southeast Asian traders, particularly from the Majapahit and later Malacca Sultanate, brought Sri Lanka into broader trade networks connecting the Indian Ocean with the South China Sea.

Thus, Sri Lanka was already a key maritime hub where diverse cultural and commercial influences converged. Unlike the European model of empire-building, pre-colonial trade networks in the Indian Ocean were based on mutual agreements, tribute systems, and decentralized power structures rather than direct conquest and occupation.

Political Landscape of Sri Lanka: A Divided Island

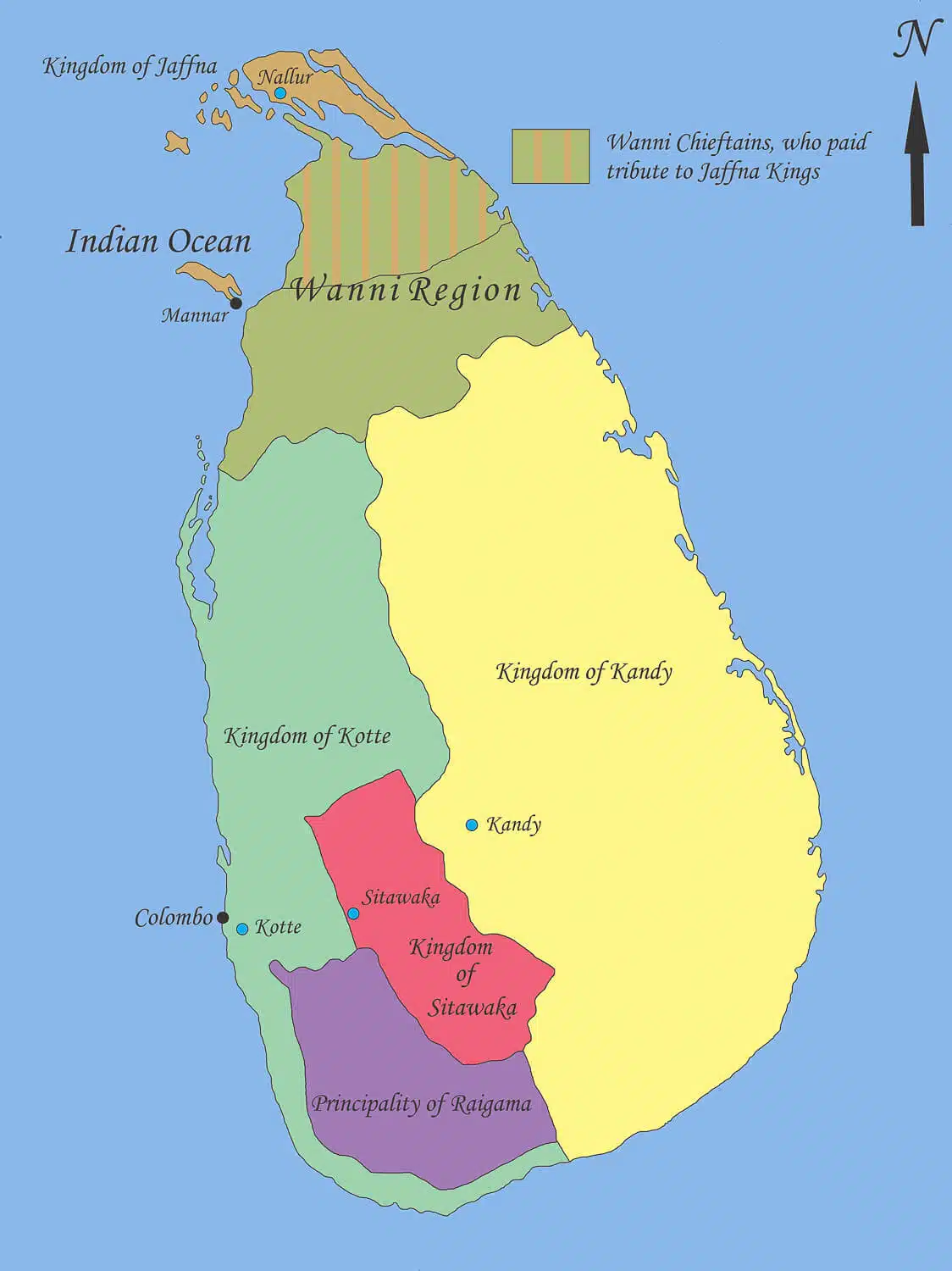

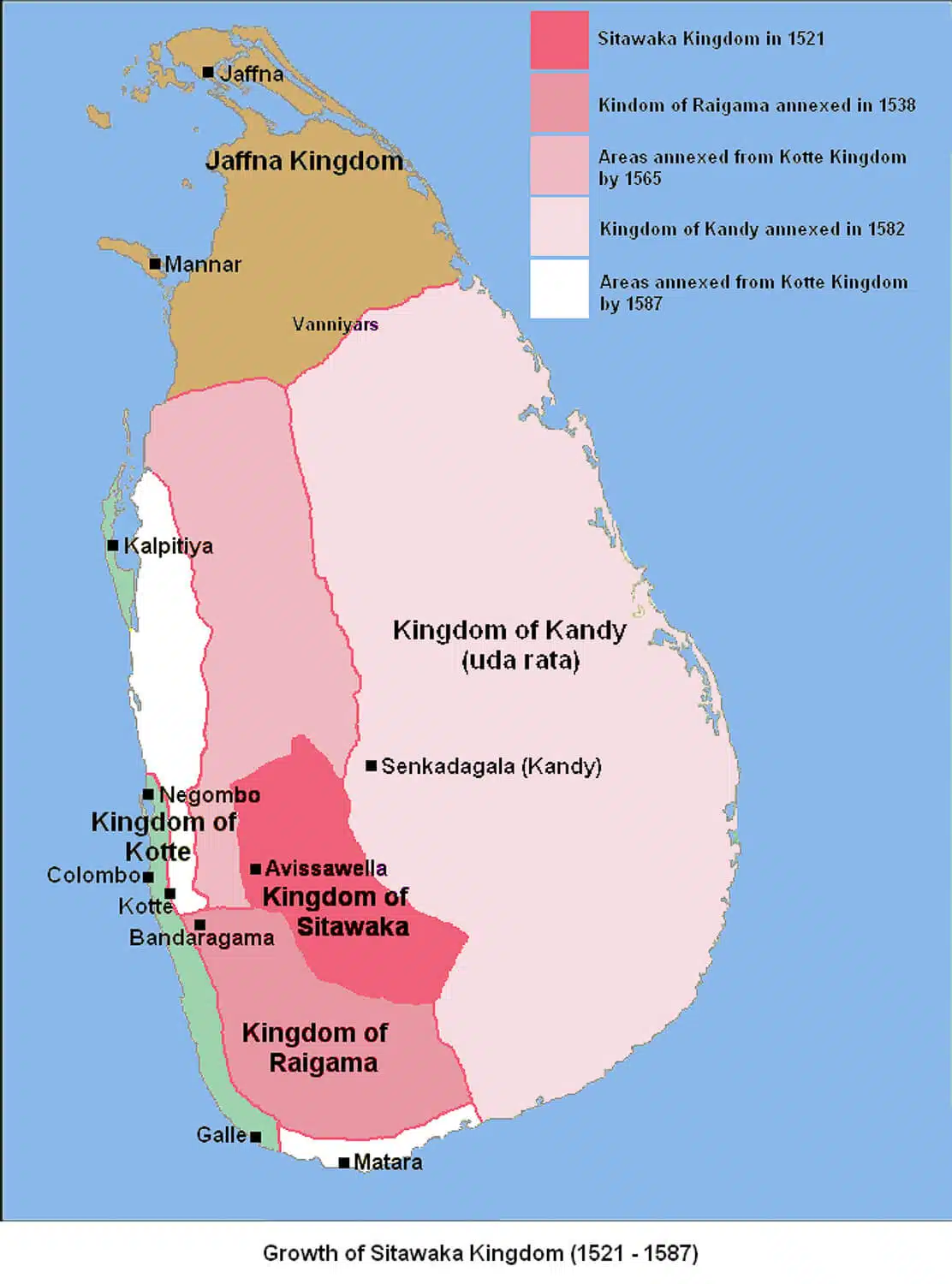

At the time of the Portuguese arrival in 1505, Sri Lanka was fragmented into several competing kingdoms, each vying for dominance:

- The Kingdom of Kotte (Southwest & Coastal Areas): The most powerful kingdom, led by King Parakramabahu VIII, controlled key ports and was deeply involved in maritime trade. However, internal divisions and succession disputes weakened its stability.

- The Kingdom of Sitawaka (Central Lowlands): A rising power under Mayadunne, this kingdom was aggressively expanding its influence, challenging both Kotte and foreign interference.

- The Kingdom of Kandy (Central Highlands): A largely isolated but resilient kingdom, Kandy maintained its independence by leveraging its mountainous terrain and strategic alliances.

- The Jaffna Kingdom (Northern Sri Lanka): A Tamil kingdom that maintained strong ties with South Indian polities, particularly the Vijayanagara Empire.

The fragmentation of the island made Sri Lanka particularly vulnerable to external powers. The Portuguese, recognizing these divisions, would later use diplomacy, military force, and religious influence to manipulate local rivalries to their advantage.

Why Sri Lanka Caught Portugal’s Attention

Portugal’s primary goal in the Indian Ocean was controlling the lucrative spice trade, but Sri Lanka held additional strategic value:

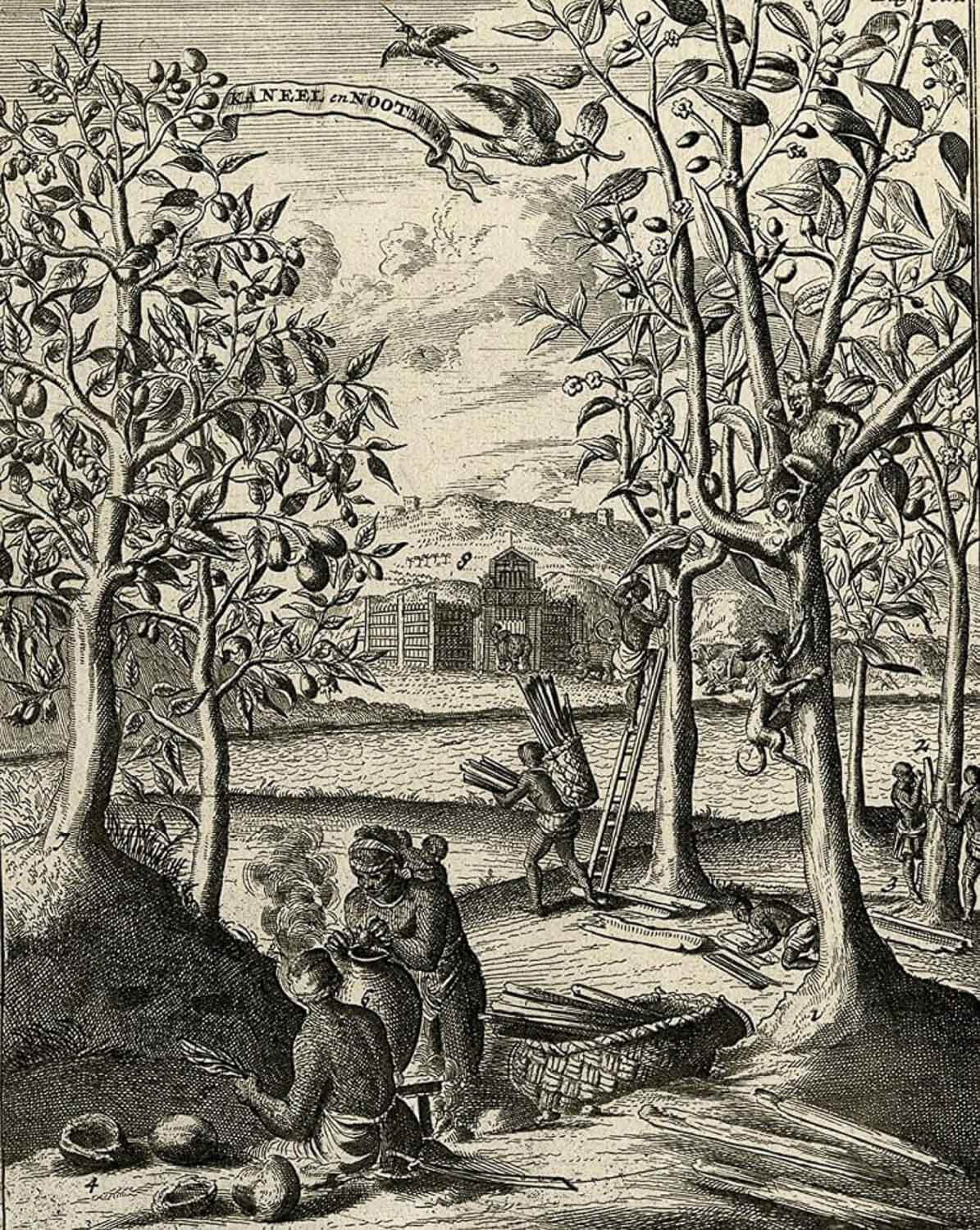

- Cinnamon Monopoly: Sri Lanka’s cinnamon was considered the finest in the world, making it an essential asset for Portuguese traders looking to dominate global spice markets.

- A Strategic Naval Base: Positioned along major Indian Ocean trade routes, Sri Lanka could serve as a military outpost to secure Portuguese sea lanes between Goa, Malacca, and the Spice Islands.

- Conversion and Influence: Portugal’s strong Catholic mission aimed to spread Christianity, and Sri Lanka’s divided political landscape provided opportunities to introduce European religious and cultural influence.

Thus, while the Portuguese first arrived in Sri Lanka by accident, it did not take long for them to recognize the island’s immense value. What began as an incidental landing in Galle or Colombo in 1505 would soon escalate into a long and often violent struggle for dominance over Sri Lanka, reshaping the island’s history forever.

First Contact and Gradual Entanglement of the Portuguese in Sri Lanka

A Gust of Wind: How the Portuguese First Reached Sri Lanka by Accident

The first recorded Portuguese contact with Sri Lanka was unintentional. In 1505, a fleet commanded by Dom Lourenço de Almeida, the son of the Portuguese viceroy of India, was caught in a storm while navigating the Indian Ocean in search of Moorish ships to attack. The storm forced the fleet to drift towards the southwestern coast of Sri Lanka, leading to an unplanned landing at Galle or Colombo (the exact location remains debated). The Portuguese sailors were initially unaware of the island’s importance, but they quickly recognized its potential as a strategic outpost in the spice trade.

Upon landing, the Portuguese encountered the Kingdom of Kotte, which controlled much of the island’s southwestern region. The ruler of Kotte, King Parakramabahu VIII (or his successor, depending on the historical account), received the Portuguese with interest, seeing them as potential allies against rival kingdoms. The Portuguese, in turn, saw an opportunity to establish trade relations and secure a foothold on the island. Their initial approach was focused on commercial interests rather than territorial conquest, but this dynamic would change in the decades that followed.

Underneath is an amazing video of how Lourenço de Almeida ended up discovering Ceylon – Honors to Flash Point History (probably one of my favourite Podcast and Youtube Historic Channels)

First Encounters: The Meeting Between the Portuguese and the Kingdom of Kotte

The Portuguese quickly realized that Sri Lanka’s wealth in spices, particularly cinnamon, made it an invaluable asset in their expanding trade network. Their first formal interactions with the Kingdom of Kotte were centered around establishing a trade agreement. The King of Kotte, eager to strengthen his position against internal and external threats, welcomed Portuguese merchants and granted them permission to engage in trade. In return, the Portuguese provided military assistance against the kingdom’s enemies, particularly the rising power of Sitawaka.

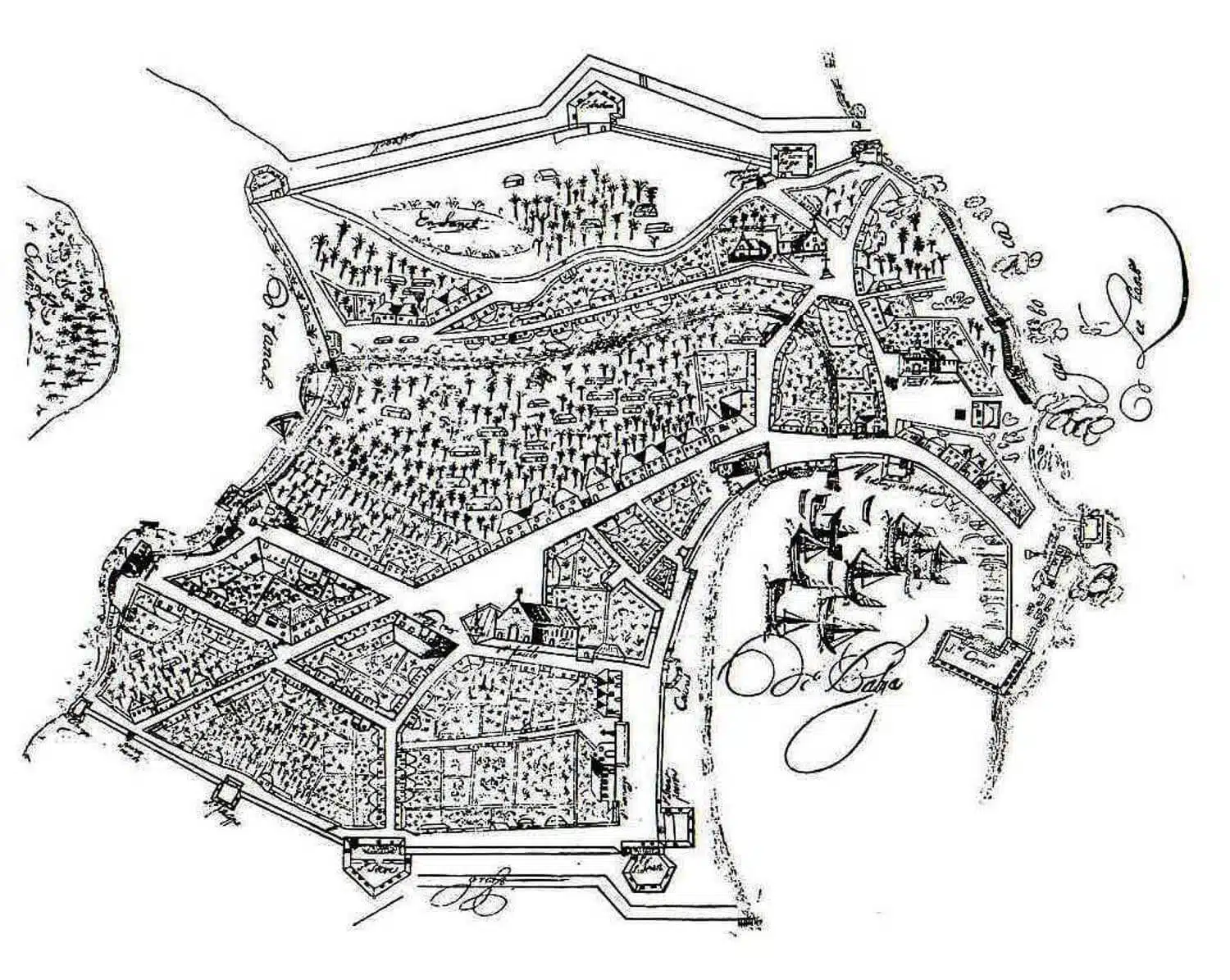

Over time, the Portuguese presence in Sri Lanka became more pronounced. They established a fortified trading post in Colombo, marking the beginning of their long-term involvement in the island’s affairs. While their initial dealings were diplomatic and trade-focused, the Portuguese gradually became entangled in Sri Lanka’s internal conflicts, using their military superiority to exert greater influence over local rulers.

Portugal’s Growing Interest in Sri Lanka

As Portugal solidified its control over major trade routes in the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka’s strategic importance increased. The island’s location made it a crucial link between Portuguese strongholds in India and their territories in Southeast Asia. Additionally, the growing demand for Sri Lankan cinnamon in European markets incentivized the Portuguese to tighten their grip on the island’s trade networks.

By the mid-16th century, the Portuguese had begun to interfere more directly in Sri Lankan politics. They supported rulers who were favorable to their interests and used their military power to suppress those who resisted. This involvement marked a transition from a commercial presence to an active political and military role in the island’s affairs. The Portuguese would soon find themselves engaged in prolonged conflicts with local kingdoms, setting the stage for a period of colonial rule.

The Portuguese in Sri Lanka: Expansion and Resistance

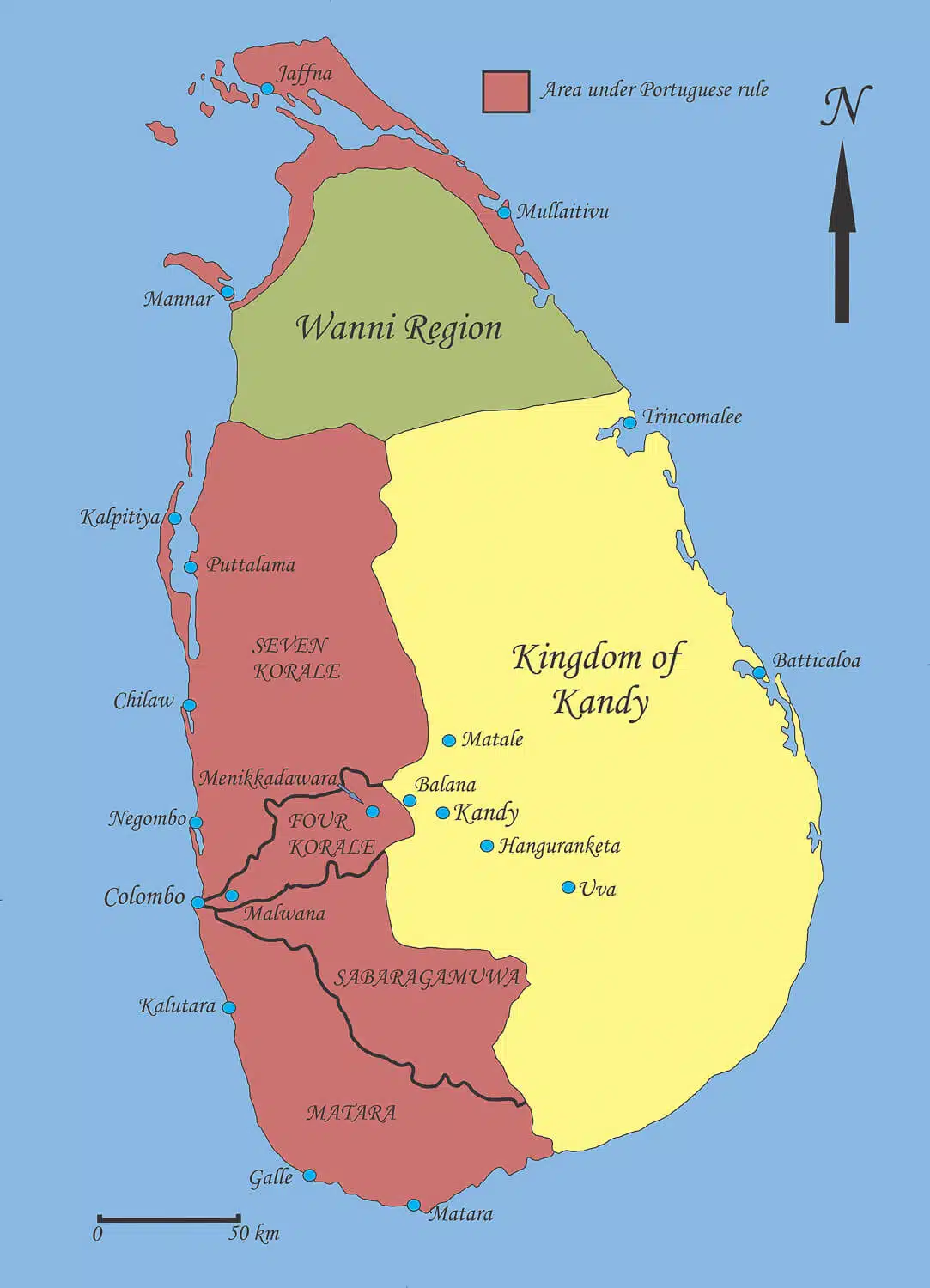

The Expansion of Portuguese Control

Following their initial foothold in Colombo, the Portuguese gradually expanded their control over Sri Lanka’s coastal regions. Their strategy relied on a combination of military force, strategic alliances, and economic pressure. The death of King Dharmapala of Kotte in 1597 marked a turning point, as he had bequeathed his kingdom to the Portuguese Crown, effectively giving them control over much of Sri Lanka’s southwestern territory.

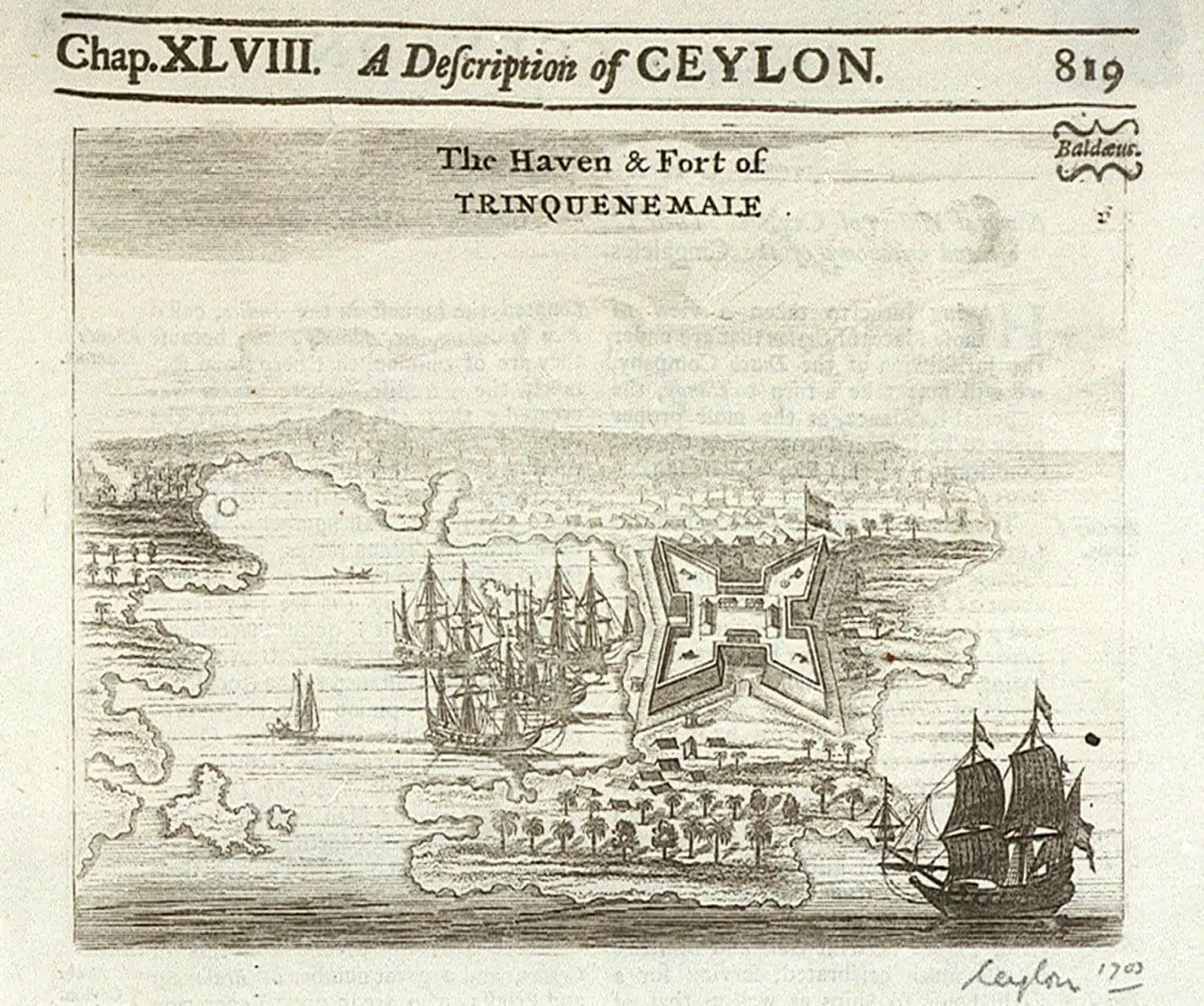

The Portuguese fortified their positions by building strongholds in key locations, including Colombo, Galle, and Jaffna. They also sought to control maritime trade by establishing a monopoly over cinnamon exports. However, their expansion was met with fierce resistance from local rulers, particularly the Kingdom of Kandy, which remained independent throughout the Portuguese era.

War, Alliances, and Resistance: The Struggle for Power

The Portuguese faced continuous resistance from Sri Lankan rulers, especially those of the Kingdom of Kandy. Several military campaigns were launched against the Portuguese, with varying degrees of success. The Kandyan kings, most notably Vimaladharmasuriya I, employed guerrilla warfare tactics, using the island’s dense forests and mountainous terrain to their advantage. The Sinhalese–Portuguese War lasted for decades, with both sides suffering heavy losses. The Portuguese were able to maintain control over coastal regions, but they struggled to penetrate the interior. Eventually, the arrival of the Dutch in the early 17th century shifted the balance of power, as the Kandyan rulers formed alliances with the Dutch to drive out the Portuguese.

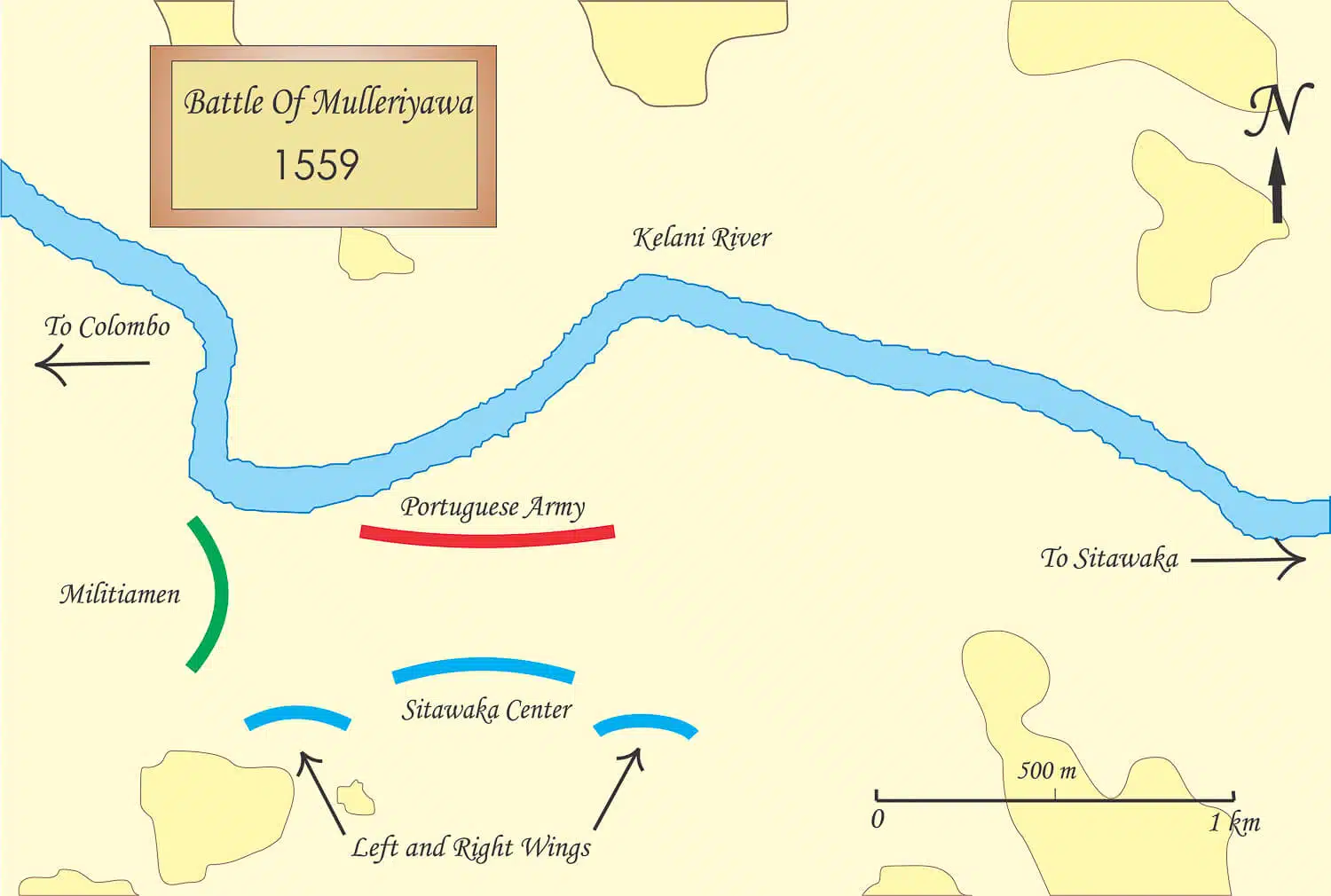

The Battle of Mulleriyawa (1559)

One of the most significant clashes in the early conflicts was the Battle of Mulleriyawa. In 1559, the forces of the Kingdom of Sitawaka, led by King Rajasinghe I, engaged the Portuguese army in a fierce battle. The battle took place near Mulleriyawa, a strategic location close to Colombo. Rajasinghe I, recognizing the importance of disrupting Portuguese control, launched a surprise attack on the Portuguese forces. The Sitawakan army, which consisted of a combination of Sinhalese soldiers and local levies, utilized their knowledge of the terrain to their advantage. They ambushed the Portuguese troops, who were caught off guard and unable to effectively deploy their superior weaponry.

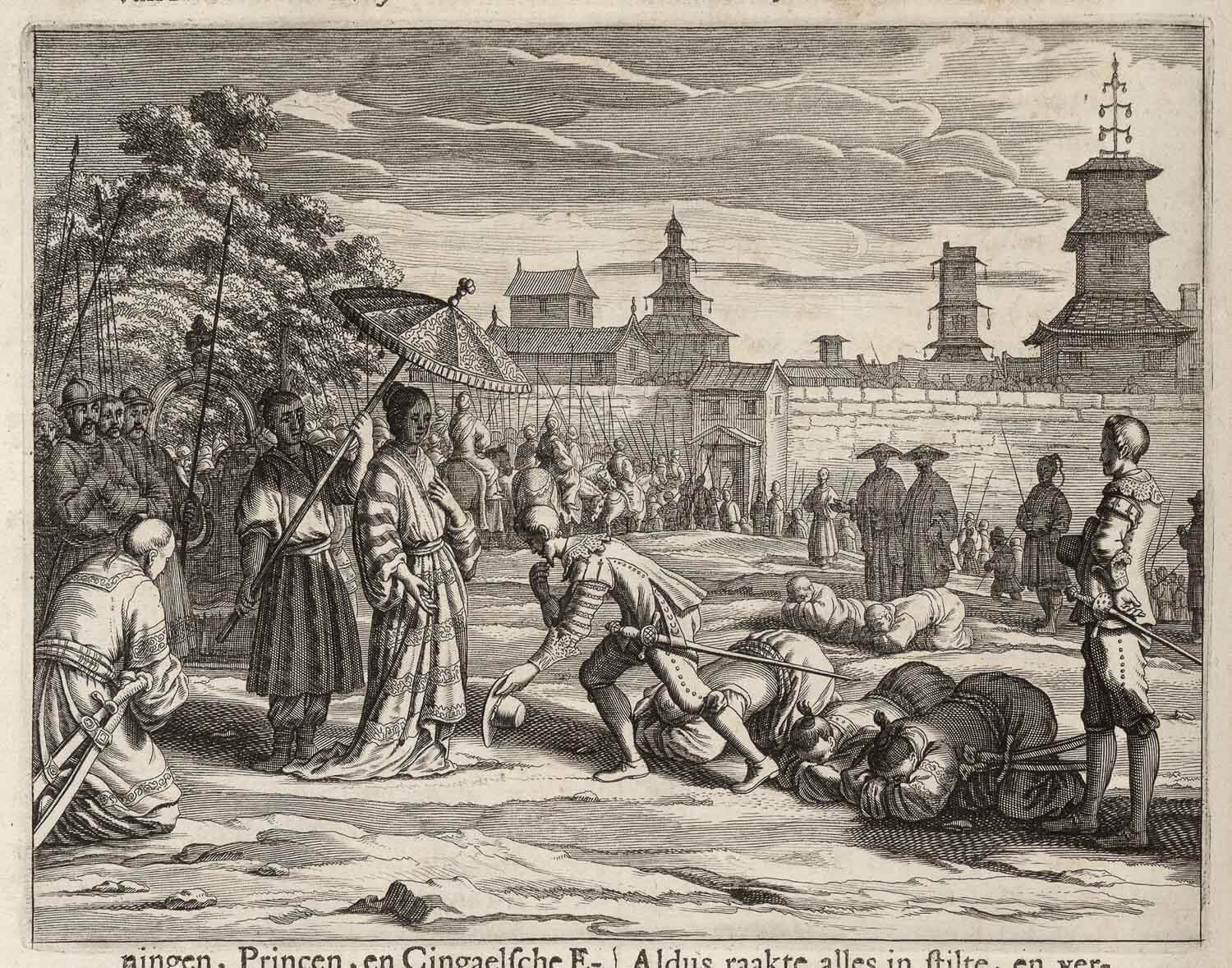

The battle was intense, with heavy fighting on both sides. The Sitawakan forces, displaying great courage and determination, pressed their attack relentlessly. The Portuguese, despite their initial shock, fought back fiercely, relying on their firearms and military discipline. However, the Sitawakan army’s superior numbers and tactical advantage eventually overwhelmed the Portuguese defenses. The Portuguese suffered heavy casualties, and their commander was killed in action. The Battle of Mulleriyawa was a major victory for the Sinhalese forces, demonstrating their capability to challenge the Portuguese.

After his victory at Mulleriyawa, Rajasinghe I sought to eliminate the Portuguese presence completely. Between 1587 and 1588, he launched a massive siege on Colombo, deploying thousands of soldiers to crush the European stronghold. The Portuguese, though heavily outnumbered, managed to withstand the prolonged siege due to their superior fortifications, naval reinforcements, and the inability of Rajasinghe’s forces to breach their defenses completely.

After nearly a year of conflict, Rajasinghe was forced to withdraw, marking a turning point. The Portuguese had demonstrated that, despite the odds, they could hold their positions. However, the war had severely weakened both sides, setting the stage for new power shifts in the coming decades.

Portuguese Expansion and the Campaign of Danture (1594)

By the late 16th century, with Sitawaka’s decline following Rajasinghe’s death, the Portuguese saw an opportunity to expand their influence inland. They planned to install a pro-Portuguese ruler in Kandy, the last independent kingdom, by using the claim of Dona Catarina, the rightful heir to the Kandyan throne. The Portuguese launched the Campaign of Danture in 1594, hoping to place her on the throne through marriage to a ruler they could control.

However, the Kandyans, led by King Vimaladharmasuriya I, fiercely resisted. Using the dense forests and mountainous terrain to their advantage, Kandyan forces ambushed the Portuguese, annihilating their invading army. The Portuguese commander, Pedro Lopes de Sousa, was killed, and the survivors were either slaughtered or captured. This crushing defeat demonstrated that Kandy would not fall easily and solidified its position as the last bastion of Sinhalese independence.

Rebellions, Treaties, and Conquest (1616–1621)

Between 1616 and 1621, the Portuguese continued their determined efforts to consolidate control over Sri Lanka, despite facing significant challenges. During this period, the Kingdom of Kandy, under King Senarat, who had succeeded Vimaladharmasuriya I, remained a formidable adversary. Senarat skillfully combined military resistance with diplomatic maneuvers in an effort to preserve his kingdom’s independence. Conflicts between Kandy and the Portuguese persisted, with both sides experiencing alternating victories and losses.

At the same time, Portuguese territories were destabilized by numerous uprisings, fueled by resentment toward their attempts to impose Catholicism and tighten administrative control over local populations. These rebellions highlighted the growing dissatisfaction among Sinhalese communities under Portuguese rule. In an attempt to stabilize their authority, the Portuguese sought to negotiate treaties with Kandy. However, these agreements were fragile and frequently broken as hostilities resumed.

Amidst this turbulent period, a significant milestone in Portuguese expansion occurred in 1619 with the conquest of the Jaffna Kingdom in northern Sri Lanka. Portuguese involvement in Jaffna had begun decades earlier when they sought to extend their influence over the Tamil kingdom. As early as 1570, they had installed Periyapulle, a ruler of their choice, on the throne of Jaffna as a puppet king. However, this arrangement proved short-lived when Periyapulle was overthrown in 1582 by Puviraja Pandaram, the son of Sankili I, who pursued an anti-Portuguese policy.

The formal conquest of Jaffna in 1619 marked the culmination of years of Portuguese interference in the region. Sankili Kumaran, who had usurped the throne at that time, sought recognition from the Portuguese but was denied. In response, Sankili Kumaran turned to the Nayaks of Thanjavur in South India for support. This act prompted a decisive Portuguese invasion. The campaign ended with Sankili Kumaran’s capture as he attempted to flee by sea, effectively bringing an end to local rule in Jaffna. The annexation of Jaffna was a critical moment for Portuguese ambitions in Sri Lanka, as it consolidated their power over the island’s western coastal regions and strengthened their maritime dominance across Ceylon. With Jaffna under their control, the Portuguese achieved a strategic advantage that further solidified their position within Indian Ocean trade networks.

The Role of Catholic Missionaries in Portuguese Ceylon

In addition to their military and economic endeavors, the Portuguese actively promoted Roman Catholicism in Sri Lanka. Missionary efforts were led by the Jesuits, Franciscans, and Dominicans, who established churches, schools, and seminaries. Many local rulers and elites converted to Christianity, particularly in coastal areas under Portuguese influence.

The spread of Catholicism had a lasting impact on Sri Lankan culture and society. Christian names became common among converts, and new religious traditions were introduced. The Portuguese also encouraged the destruction of Buddhist and Hindu temples, leading to significant cultural shifts in certain regions.

Here’s an exciting work about the Missionary Churches in Ceylon – Remains of Dark Days: The Architectural Heritage of Oratorian Missionary Churches in Sri Lanka

Life Under Portuguese Rule

Portuguese rule brought significant changes to Sri Lankan society. The introduction of European administrative systems, land ownership practices, and trade policies altered traditional ways of life. Many local communities were forced into labor-intensive cinnamon production, while others were displaced due to Portuguese military campaigns.

Despite the challenges, Portuguese influence also brought new architectural styles, culinary traditions, and linguistic elements that remain part of Sri Lankan culture today. However, resentment towards foreign rule continued to grow, ultimately leading to the Portuguese being ousted by the Dutch in 1658.

The Fall of The Portuguese in Sri Lanka

The Rise of the Dutch and the Fall of the Portuguese

By the early 17th century, the Portuguese faced increasing challenges to their dominance in Sri Lanka. The Kingdom of Kandy, under leaders such as Vimaladharmasuriya I, persistently resisted Portuguese expansion into the island’s interior. Recognizing the need for external assistance to expel the Portuguese, the Kandyan rulers sought alliances with other European powers. This led to a strategic partnership with the Dutch East India Company (VOC), which was eager to undermine Portuguese influence in the region and secure access to the lucrative spice trade.

The Dutch-Kandyan alliance culminated in a series of coordinated military campaigns against Portuguese strongholds. The combined forces targeted key coastal forts and trading posts, systematically weakening Portuguese control. A pivotal moment occurred in 1656 with the fall of Colombo, the primary Portuguese bastion on the island. After a prolonged siege, Dutch forces captured the city, effectively ending Portuguese rule in Sri Lanka. By 1658, the remaining Portuguese territories had fallen, and the Dutch established themselves as the new colonial power on the island.

The Lasting Impact of Portuguese Rule

The Portuguese presence in Sri Lanka, spanning over a century, left an indelible mark on the island’s cultural, religious, and social landscape. One of the most significant legacies was the introduction and spread of Roman Catholicism. Missionary efforts led to the conversion of segments of the population, particularly in coastal areas, and the establishment of churches and religious institutions that continue to function today.

Linguistically, the Portuguese influence is evident in the incorporation of Portuguese loanwords into the Sinhala and Tamil languages. Many Sri Lankans, especially among the Burgher community, bear Portuguese surnames, reflecting the intermarriages and cultural assimilation that occurred during this period. Architecturally, remnants of Portuguese fortifications and buildings dot the coastal regions, showcasing a blend of European and local design elements.

The Legacy of The Portuguese in Sri Lanka

The Portuguese presence in Sri Lanka from 1505 to 1658 left a lasting and multifaceted legacy that continues to shape the island’s cultural, administrative, and linguistic landscape.

Administrative and Social Structures

The areas the Portuguese claimed to control in Sri Lanka were part of what they majestically called the Estado de India (state of India), and were governed in name by the viceroy in Goa, who represented the king. The Portuguese did not try to alter the existing basic structure of native administration. The island was divided into four dissavanis, or provinces, each headed by a dissava. These dissavanis included areas like Colombo, Galle, and Jaffna after its conquest. The Caste system remained intact, and all obligations that had been due to the sovereign now accrued to the Portuguese state.

Economic Impact

Cinnamon and elephants became articles of Portuguese monopoly; they provided good profits, as did the trade in pepper and Betel nuts (Areca nuts). Portuguese officials compiled a Tombo (land register), to provide a detailed statement of landholding, crops grown, tax obligations, and nature of ownership.

Religious and Educational Influence

The period of Portuguese influence was marked by intense Roman Catholic missionary activity. Franciscans established centers from 1543 onward, with Jesuits, Dominicans, and Augustinians arriving later. The Portuguese missionaries successfully converted almost the entire island of Mannar to Roman Catholicism by 1544. By 1602, Jesuit influence led to significant changes in education, incorporating Sinhalese culture into singing. The Portuguese implemented two main types of schools: Parish Schools and Colleges, using the Jesuit teaching technique.The main teaching technique came from the Jesuit Order.

Father Francisco Xavier who understood some parts of the Sinhalese culture embedded that knowledge into singing . Further, to those who learnt such subjects, Latin too was taught. This was intermingled with religious belief.The medium of the Jesuit education system was solely the Portuguese language and also Sinhala and Tamil.

While the Augustinians’ convent was based in Rambukkana, the Dominicans focused their efforts on Jaffna and Galle. They emphasized comprehensive education that extended beyond just reading, writing, and singing.

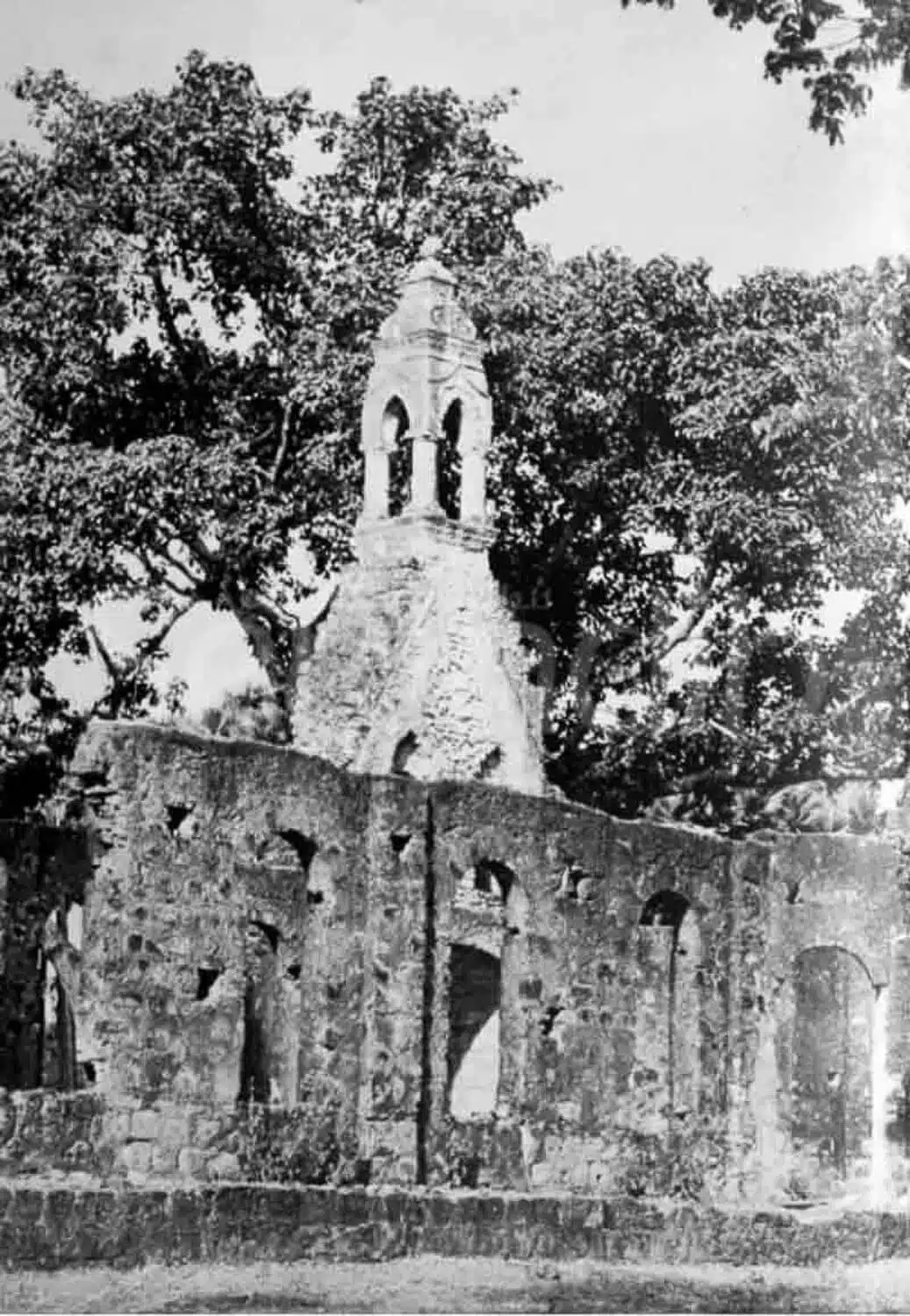

The Dutch occupied the region from the mid-17th century until the late 18th century. During the first hundred years of their rule, they were reportedly satisfied with repurposing the many Portuguese churches for the Dutch Reformed faith. As Ronald Lewcock (1988, p.122) notes, “The buildings were often re-decorated and sometimes given entirely new facades.”

Notable remnants of Portuguese religious architecture include:

- The ruins of the old Portuguese Church of Holy Trinity in Chankanai (1641)

- The remains of a Portuguese Church at Myliddy in Jaffna (1644)

- The still-standing Church of St. James in Kilaly (1610-1620)

- The wooden retable at the Church of Our Lady of Victory in Pesalai is also a notable example.

Linguistic Contributions

The interaction of the Portuguese and the islanders led to the evolution of a new language, Portuguese Creole. Speakers of Portuguese Creole are generally members of the Burgher Community. In Puttalam, Portuguese Creole consists of words from Portuguese, Sinhala, Tamil, and even Dutch and English. It is considered to be the most important creole dialect in Asia because of its vitality and the influence of its vocabulary on the Sinhala language.

Many Sinhala words are of Portuguese origin, these are called “loan words” as they termed by lexicographers that rarely appear in the same form as the original; the vast majority have undergone naturalization. Examples include:

- Almariya (armário – wardrobe)

- Annasi (ananás – pineapple)

- Baldiya (balde – bucket)

- Bankuwa (banco – bench)

- Bonikka (boneca – doll)

- Bottama (botão – button)

- Gova (couve – cabbage)

- Kabuk (caboco – laterite, a building material)

- Kalisama (calças – trousers)

- Kamisaya (camisa – shirt)

- Kussiya (cozinha – kitchen)

- Lensuwa (lenço – handkerchief)

- Masaya (mês – month)

- Mesaya (mesa – table)

- Narang (laranja – orange)

- Nona (dona – lady)

- Paan (pão – bread)

- Pinturaya (pintura – painting)

- Rodaya (roda – wheel)

- Rosa (rosa – rose/pink)

- Saban (sabão – soap)

- Salada (salada – salad)

- Sapattuwa (sapato – shoe)

- Simenti (cimento – cement)

- Sumanaya (semana – week)

- Toppiya (hat)

- Tuwaya (toalha – towel)

- Viduruwa (vidro – glass)

Surnames

Portuguese surnames are still common in Sri Lanka. Here are some examples:

- Corea (Correia)

- Croos (Cruz)

- De Abrew (Abreu)

- De Alwis (Alves)

- De Mel (Melo)

- De Saram (Serra)

- De Silva (Silva)

- De Soysa or De Zoysa (Sousa)

- Dias (Dias)

- De Fonseka or Fonseka (Fonseca)

- Fernando (Fernandes)

- Gomes or Gomis (Gomes)

- Mendis (Mendes)

- Perera (Pereira)

- Peiris or Pieris (Pires)

- Rodrigo (Rodrigues)

- Salgado (Salgado)

- Vaas (Vaz)

Cuisine

Those who assume that Sri Lanka’s hot curries were the creation of the Islanders will be surprised to learn that the Portuguese introduced chillies to the local cuisine. Portuguese cakes, such as bolo fiado or bolo folhado, a layer cake filled with cadju (cashews), and sweets such as borowa – biscoitos de sêmola (the name might be a derivation from Broa bread), and fugete (perhaps derived from the Foguetes de Amarante sweets), as well as lingus sausage (perhaps derived from Linguiça sausage) and pastries. Many foods of Portuguese influence are still popular in Sri Lanka.

Music and Dance

The Portuguese importation of rhythmic instrumental dance music called “Baila”, which was popular with the Portuguese traders and their Kaffir slaves was significant. Characterized by its upbeat 6/8 time, Baila has today become a fashionable genre of Sri Lankan music. The Portuguese Burgher community played a key role in keeping Baila alive, continuing to write and perform songs from as early as the 1850s through the 20th century.

This song, Minha Amor, is part of the Baila tradition and is sung in Sri Lankan-Portuguese Creole. If you know Portuguese, you can understand big parts of the lyrics. Showcasing songs like this is important in keeping a unique musical and linguistic heritage from fading away.

The Lyrics (and an attempt of a direct translation):

“Vi Minha amor par baila (Come dance with me my love)

Dose Minha coracao ta desia (sweetheart of mine, I was telling you)

Tem este dia nossa alagria (this is a joyful day)

Vi minha juntu par baila” (come dance close to me)

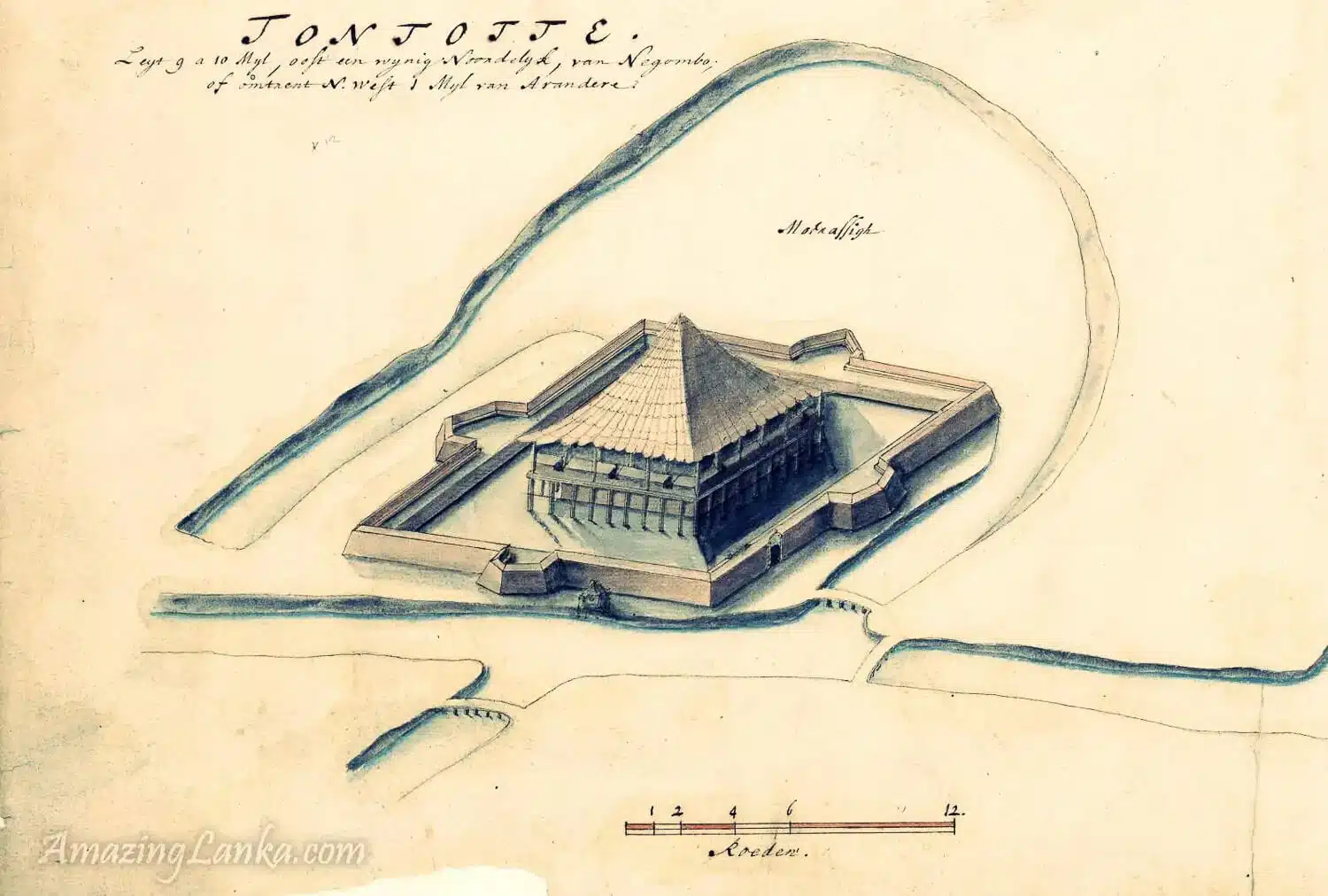

Architecture and Fortifications

The Portuguese legacy includes several fortifications, such as:

- Colombo Fort (1518, 1544)

- Matara Fort (1550)

- Mannar Fort (1560)

- Galle Fort – Black Fort (1588)

- Ruwanwella Fort (1590s)

- Hanwella Fort (1597)

- Menikkadawara Fort (1599)

- Fort Hammenheil (1618)

- Jaffna Fort (1618)

- Ratnapura Fort (1618, 1620)

- Fort Frederik (1624)

- Batticaloa Fort (1628)

- Kayts Island Fort (1629)

- Haldummulla Fort (1630)

- Kotugodella Fort (1630)

- Kalutara Fort (1655)

- Arandora Fort

- Arippu Fort

- Delft Island Fort

- Pooneryn Fort

- Negombo Fort (destroyed and rebuilt by the Dutch in 1672)

The Black Fort in Galle, also known as Santa Cruz Fort, features a real Portuguese fortress, including tunnels, secret cubicles, and masonry work constructed at different strategic points. The outer wall of the bastion is built of coral stone using lime and sand as binding material. The underground chambers were previously used for defense and storage. The lower terrain indicates they were meant for the eight cannons placed in the direction of the Port. The upper levels of the curved ramparts connect to the lower levels by a subterranean passage plastered and whitewashed, making room for any soldier to comfortably get at the lower levels.

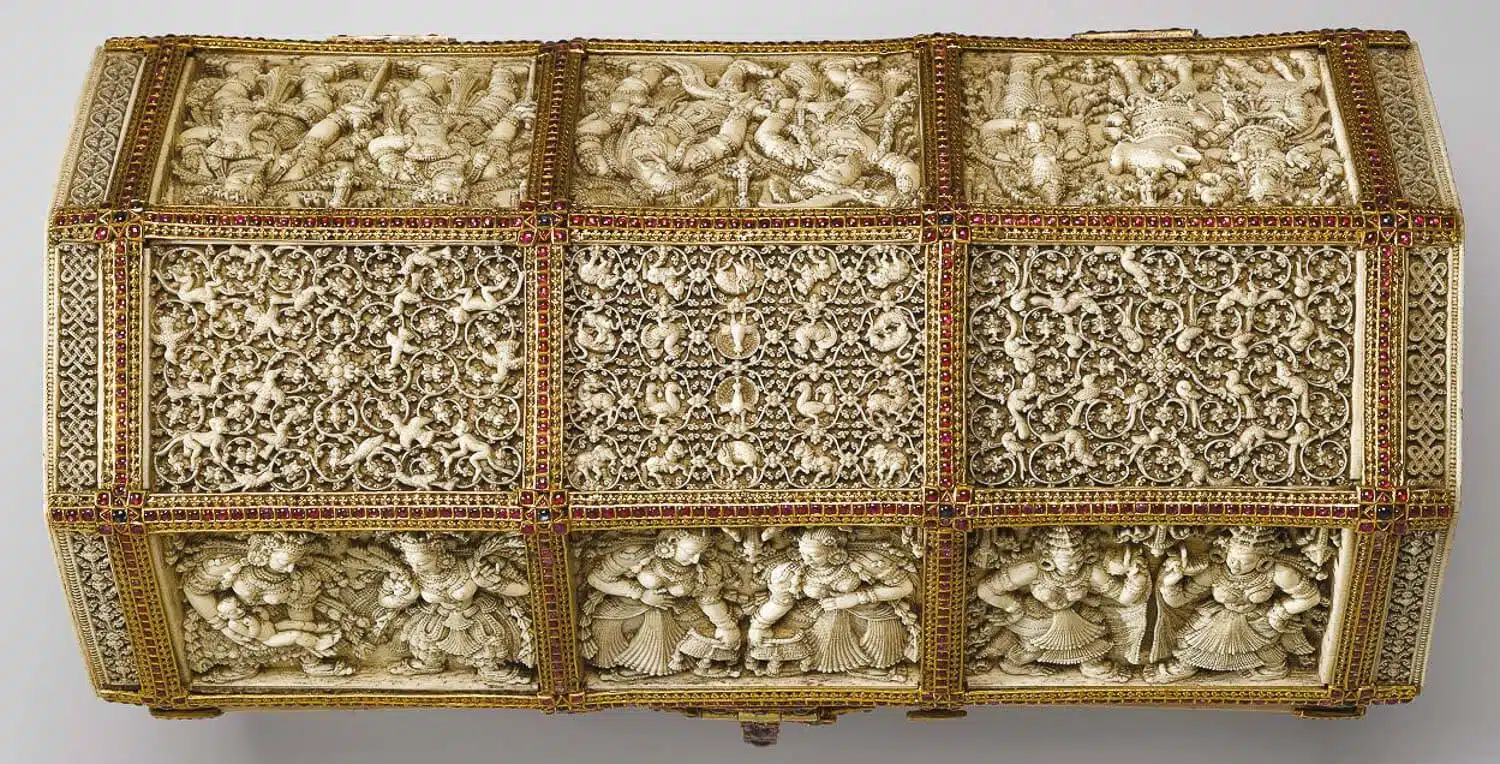

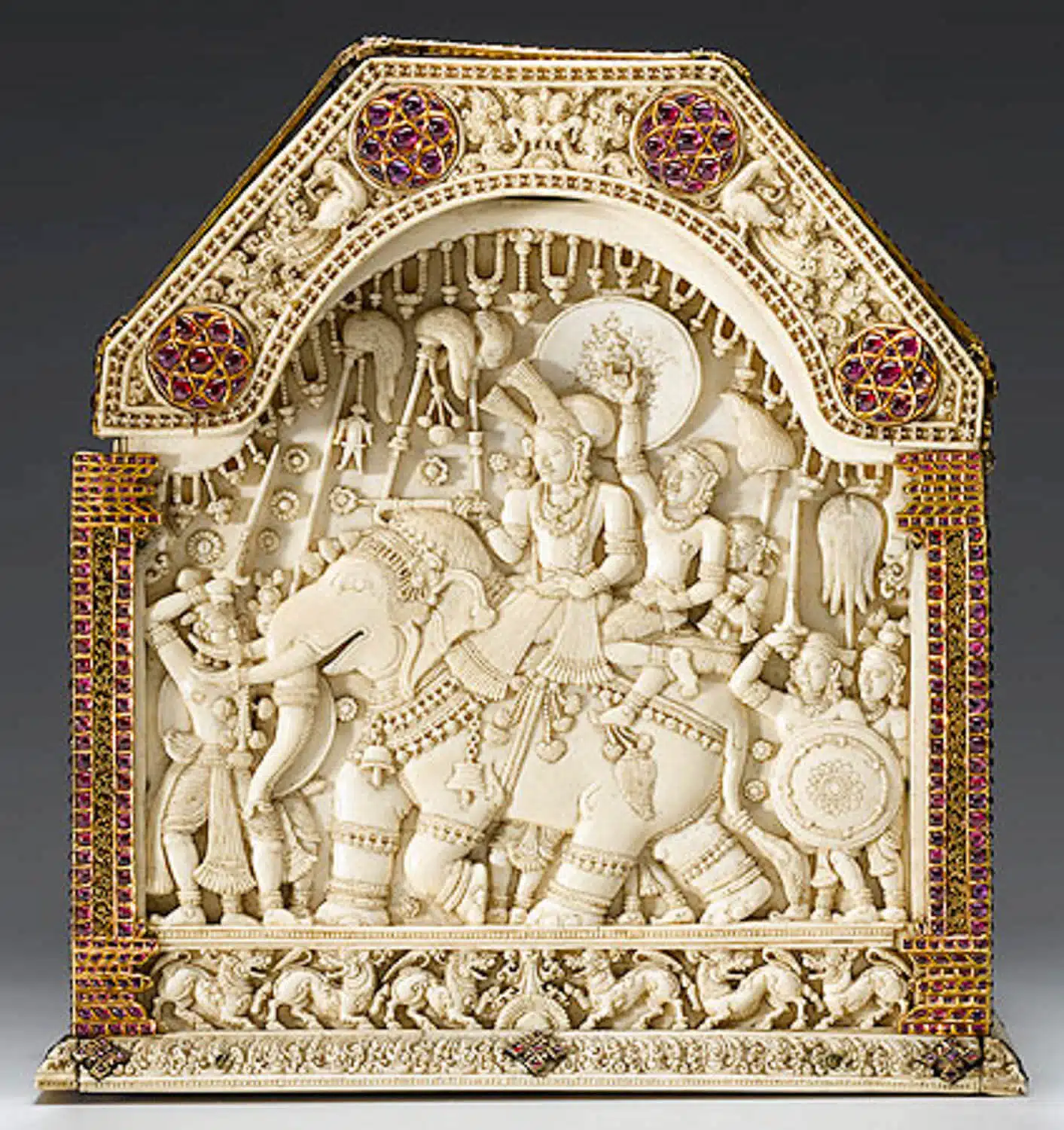

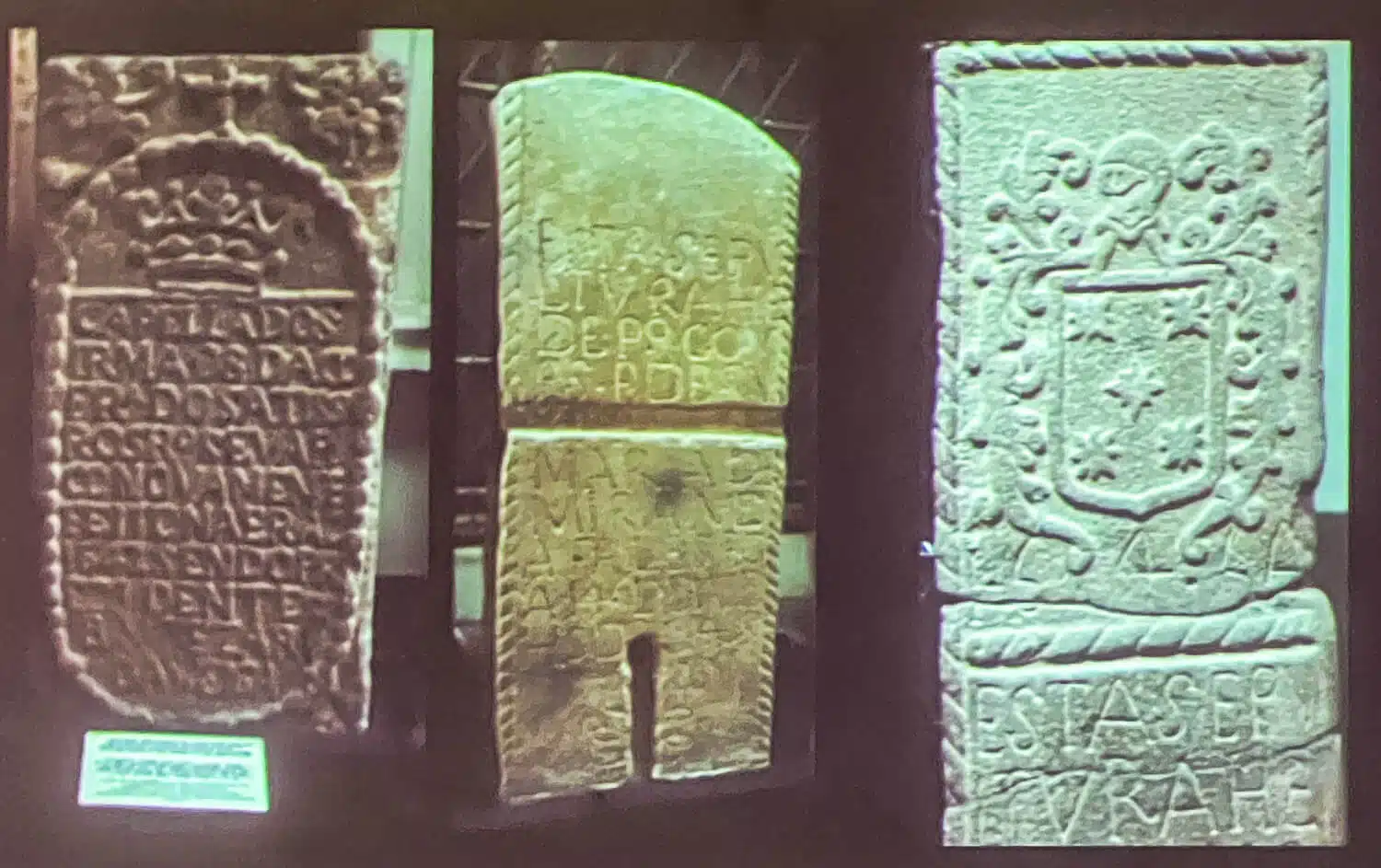

Artifacts and Inscriptions

Artifacts from the Portuguese period include:

- The Coronation Casket (1541) – (Schatkammer der Residenz, Munich): This ivory casket depicts Prince Dharamapala being crowned by King John III and receiving the King’s blessings. The box was made at the court of the king of Kotte and sent to Portugal as an ambassador gift, which had conquered Ceylon at the beginning of the 16th century. The ivory carvings show the embassy, but also dancers, musicians, an elephant ride, and scenes of homage and prayer. It was given to Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria in the 16th century.

- 17th-century wood carvings of Portuguese soldiers at Embekke Devale.

- Depictions of Portuguese and Sinhala soldiers at Saman Devala Ratnapura.

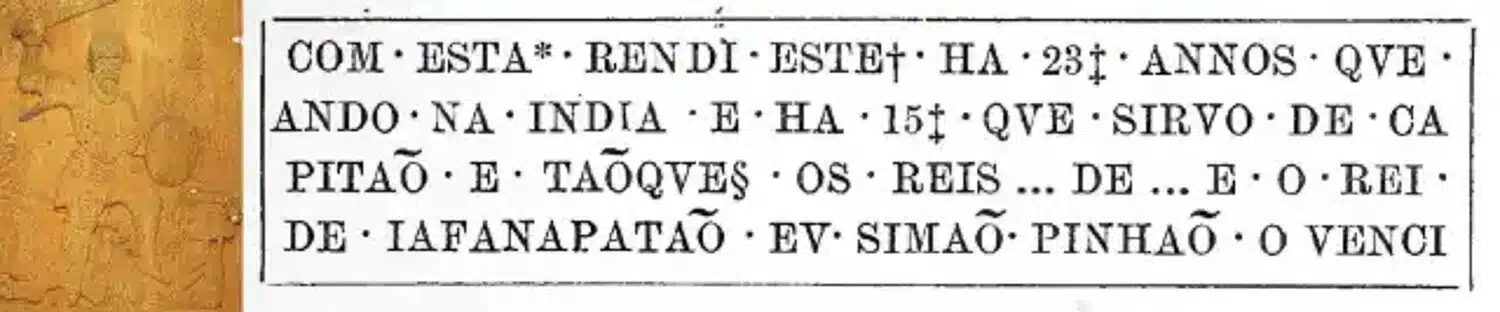

- Portuguese Inscriptions: Few vestiges of inscribed tombstones and other records are of great importance as historical records.

- Royal Arms of Portugal (1598) from Mankadavara.

- Coins used in the Portuguese Period: Malacca, Ginimessa, Saint type coins – Gold, Panam, Gold Pagodi, Tanga, Larins.

Bibliography

Here are the main articles used as references for this article. Special thanks to the Tourism Board of Sri Lanka, together with the National Museum of Colombo, which made an amazing presentation on our press trip about the “Portuguese in Ceylon”:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/ – Sinhalese-Portuguese Conflicts

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/ – The Fall of the Portuguese in Ceylon

- https://www.britannica.com/ – The Portuguese in Sri Lanka – The History of Sri Lanka

- https://www.icm.gov.mo/ – The Rise and Fall of the Portuguese Language in Sri Lanka

- https://www.ceylondigest.com/ – The Portuguese Burghers of Sri Lanka

- https://amazinglanka.com/ – Heritage and Monuments of Sri Lanka

- https://www.jaffnaroyalfamily.org/ – Historical Images of Jaffna and Sri Lanka

- http://en.wikipedia.org/ – Portuguese Forts

- https://repositorio.ulisboa.pt/ –

Remains of Dark Days: The Architectural Heritage of Oratoria – JAYASINGHE, Sagara; SANTOS, Joaquim Rodrigues dos; CARITA, Hélder.

Plan your next adventure with us!

Here are the links we use and recommend to plan your trip easily and safely. You won’t pay more, and you’ll help keep the blog running!

Adventures in Sri Lanka - The Ancient Ceylon

Explore The Galapagos Islands

Hiking in Switzerland & Italy

The Hidden Worlds of Ecuador

ABOUT ME

I’m João Petersen, an explorer at heart, travel leader, and the creator of The Portuguese Traveler. Adventure tourism has always been my passion, and my goal is to turn my blog into a go-to resource for outdoor enthusiasts. Over the past few years, I’ve dedicated myself to exploring remote destinations, breathtaking landscapes, and fascinating cultures, sharing my experiences through a mix of storytelling and photography.

SUBSCRIBE

Don’t Miss Out! Be the first to know when I share new adventures—sign up for The Portuguese Traveler newsletter!

MEMBER OF

RECENT POSTS

COMMUNITY

TRAVEL INSURANCE

Lost luggage, missed flights, or medical emergencies – can you afford the risk? For peace of mind, I always trust Heymondo Travel Insurance.

Get 5% off your insurance with my link!