The Route of: Nellie Bly

Who was the famous Nellie Bly and how was her route?

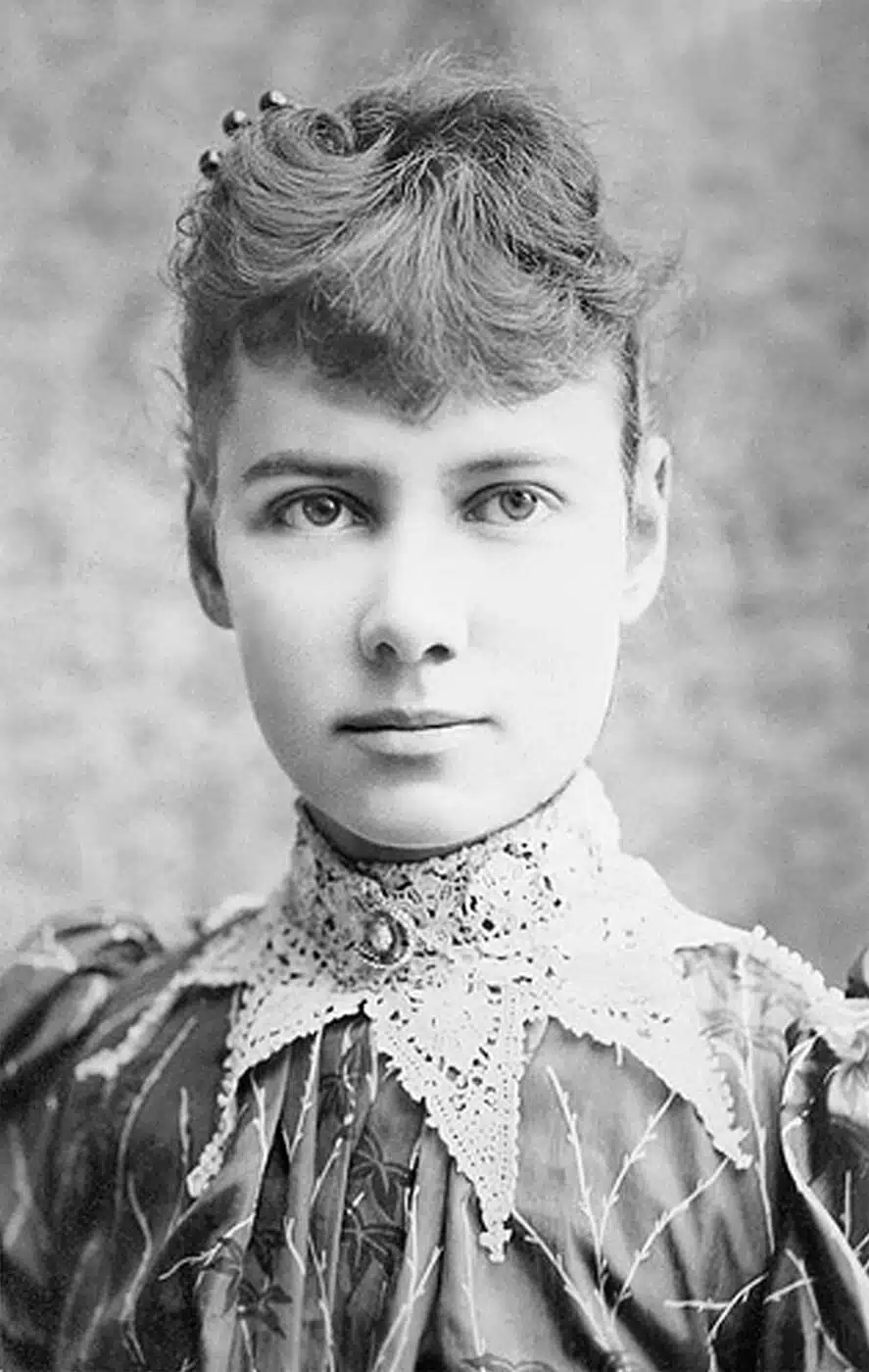

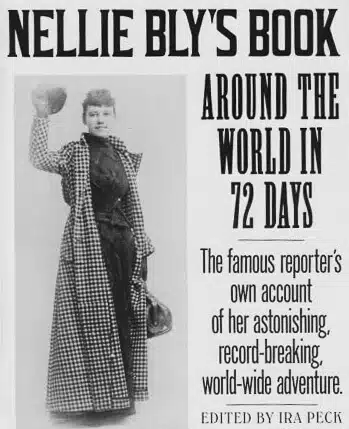

Nellie Bly (1864-1922) was an American journalist that gained Worldwide recognition after breaking the world record for the fastest trip around the world in only 72 days, successfully beating the fictitious record of Phileas Fogg in the famous novel of Jules Verne “80 Days Around the World“.

Bly was born Elizabeth Jane Cochran, one of 15 children, in Cochran’s Mills, Pennsylvania. After her father passed away she moved with her mother to Pittsburgh, where she got her first connection with the Journalism field. After reading a newspaper column in the Pittsburgh Dispatch entitled “What Girls are Good For” reporting that “girls were principally for birthing children and keeping house” she promptly wrote a response under the pseudonym “Lonely Orphan Girl”.

The editor of the newspaper was so impressed with the passion that quickly issued an advertisement asking for the author to identify herself. She was then invited to write another article that spoke about how divorce affected women, arguing the reform of divorce laws. With this last article, she finally got a full-time job at the Dispatch and her editor decided to give her a pen name, for it was customary at that time for women who were newspaper writers to have one. After the popular song “Nelly Bly” by Stephen Foster, she was named Nelly Bly, and by spelling mistakes, she became Nellie Bly.

How did Nellie Bly become a pioneer in Investigative Journalism?

Bly focused her early investigative work on the lives of women as factory workers. That soon received complaints from factory owners and she was reassigned to women’s pages to cover fashion society, and gardening, a usual role for women journalists at that time.

She became dissatisfied and decided to travel to Mexico to serve as a foreign correspondent. She was determined “to do something no girl has done before”. She spent nearly half a year reporting the lives and customs of the Mexican people. In one report she criticized the Mexican government, at the time a dictatorship under Porfirio Díaz. She was later threatened with arrest and had to flee the country. Back home she accused Díaz of being “a tyrannical czar suppressing the Mexican people and controlling the press.”

Ten Days in a Mad House.

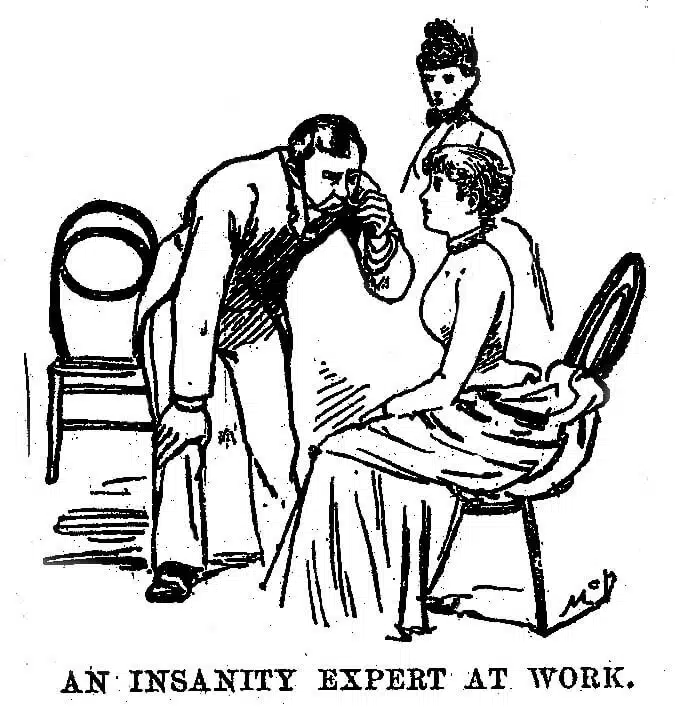

The pièce de résistence on Bly’s investigative journalism career came with the report she did on the brutality and neglect at the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island, in New York City, later a book called “10 Days in a Mad House”.

After leaving Pittsburgh, in 1887, Bly roamed to New York City where she started working in the offices of Joseph Pulitzer‘s newspaper the New York World and took an undercover assignment for which she agreed to feign insanity to investigate the reports on Blackwell’s Island’s Asylum.

In order to be admitted to the asylum she checked herself into a boarding house where she pretended to be a disturbed woman and began making accusations that the other boarders were not sane, she refused to sleep and scared so many people in the building that they eventually had to call the police and take her to the nearby courthouse, where once examined, was redirected to Blackwell’s Island.

In the asylum, Bly experienced the deplorable conditions firsthand and after 10 days she was finally released at the New York World‘s behest. Her work was a success, causing a sensation, forcing the asylum to implement reforms.

Around the World in 72 Days

In 1888 Nellie Bly suggested to her editor that she take a trip around the world in an attempt to turn the fictional novel of Jules Verne, Around the World in Eighty Days into fact for the first time. A year later, at 9:40 a.m. on November 14, 1889, she boarded the steamship Augusta Victoria, and began her 40,070-kilometer journey around the world.

She left Hoboken, New Jersey with the dress she was wearing, an overcoat, changes of underwear and a small travel bag with her toiletry essentials. She carried with her most of her money, around £200 in English bank notes and gold as well as some American currency.

The New York newspaper Cosmopolitan also sponsored its own reporter, Elizabeth Bisland, to try and beat the fictional record as well as the one of her colleague. Bisland started exactly on the same day as Bly but traveled to the opposite direction of hers.

Bly, however, was only aware that a competition was taking place once she arrived in Hong Kong and was told that Bisland had already passed by three days ago and that she was gonna lose the race. Which she promptly said, “I would not race if someone else wants to do the trip in less time, that is their concern”.

Nellie Bly's Route:

- Cochran’s Mills, Pennsylvania, USA

- New Jersey, New York, USA

- London/Dover, United Kingdom

- Calais/Paris/Amiens, France

- Brindisi, Italy

- Suez Canal, Egypt

- Aden, Yemen

- Colombo, Sri Lanka

- Penang, Malaysia

- Singapore, Singapore

- Hong Kong, Hong Kong

- Yokohama/Tokyo, Japan

- San Francisco, California, USA

- New Jersey, New York, USA

The Journey around the world.

Bly’s journey was a success due to the vast variety of transports she could get at her time. Since the invention of airplanes only took place a couple of years later she had to figure out where the fastest routes and most efficient ports and stations to depart were. For the long distances, her main transportation was the steamship but she had ultimately to take a whole variety of vehicles in order to reach other not so connected places. The reports of her journey included steam trains, ferries, rickshaws, horses and donkeys.

She left New Jersey on the steamship Augusta Victoria and had to endure seven days of seasickness in order to reach London, UK. Already in London, she took a ferry across the English Channel probably from Dover to Calais, France and in Calais, she took a train to Paris. In Paris, she did a small side trip to visit Jules Verne in Amiens and told him about her journey, to which he wished her the best of luck saying, “If you do it in seventy-nine days, I shall applaud with both hands.”

She then moved on through Europe and took a train down to Southeast Italy, to the port city of Brindisi, in Apulia. From there she took a steamship to Egypt so she could make the Suez Canal passage. Crossed the entire Red Sea with Medina and Mecca on one side and Sudan, Eritrea and Somalia on the other and reached Yemen‘s Aden Port. She then caught another ship through the Arabian Sea to Colombo in Sri Lanka (in that time under British colonial rule known as Ceylon), from Colombo she went to the British Straits Settlements of Penang and Singapore, where she bought herself a monkey that would travel on with her.

From Singapore Bly traveled to Hong Kong, where she got to know about her competitor Bisland and also had the time to visit a leper colony in China, probably next to Hong Kong in the region of Guangdong.

After Hong Kong she took another ship to the Port of Yokohama, 30 km’s away from Tokyo, in Japan where she fell in love with the place and its people, she said: “If I loved and married, I would say to my mate: ‘Come I know where Eden is'”. She called it “the land of love-beauty-poetry-cleanliness” She idolized the people “charming, sweet, happy, cheerful, delightful, graceful, pretty, artistic, obliging and progressive.” and finally saying “In short, I found nothing but what delighted the finer senses while in Japan”.

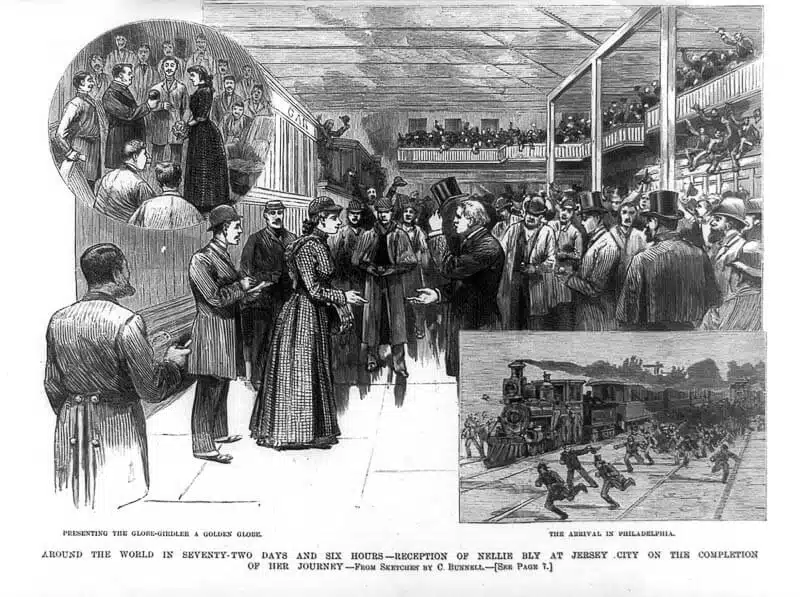

Bly then made her final leg, to the United States, unfortunately catching rough weather on the Pacific and arriving in San Francisco on January 21, two days behind schedule. She was welcomed in apotheosis, and after one last chartered train to New Jersey, officially beat the fictitious world record, not only by one day but by 8 days. Making it a 72 days trip around the world and for sure forcing Mr. Verne out of his chair to applaud her great result!

Her competitor, unfortunately, lost the race arriving four and a half days later than Bly.

After Bly many others tried and beat her record, George Francis Train (that had done his first trip in 1870, in 80 days, and was probably the person who inspired Jules Verne) did it half a year later, in 67 days, 12 hours and 3 minutes, one year later, in 1891, did it again with 64 days, the group Andre Jaeger-Schmidt, Henry Frederick and John Henry Mears did it in 1913 with only 36 days and the final record without an air vehicle was beaten by John Henry Mears in 1928 with 23 days, 15 hours, 21 minutes and 3 seconds.

The still standing record for the circumnavigation of the globe was achieved by AirFrance with its airplane Concorde, the record is of 32 hours, 49 minutes and 3 seconds, in 1992.

After her trip, Bly married a millionaire manufacturer twice her age and when he died, she succeeded him as head of the company, which after the development of multiple patents, granted her also the title of inventor.

Bly became one of the leading women industrialists in the United States and back in the journalism field she wrote stories on Europe’s Eastern Front during World War I. She was also one of the first foreigners to visit the war zone between Serbia and Austria and covered the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913 in Washington, D.C.

And that’s it, the life and route of one of the most intrepid, daredevil, feminist women of her time.

Would you dare to do the same trip that she did? What other journeys do you think nowadays one could do that would match the challenge she had at her time? I would love to hear those ideas!

In the meanwhile, for inspiration, you might want to check the Routes of Vasco da Gama, Marco Polo, or Blackbeard.The Portuguese Traveler

Plan your next adventure with us!

Here are the links we use and recommend to plan your trip easily and safely. You won’t pay more, and you’ll help keep the blog running!

Car Rental: Rent the perfect car for your trip with Discovercars.

Accommodation: Book your hotels with Booking.com or Expedia. For hotels in Asia, we usually reserve with Agoda.

Flights: We usually get our flight tickets through Booking.com or directly with the airlines for the best options and flexibility. If a flight is canceled or delayed, we use Airhelp for compensation.

Tours and Tickets: Book your tours and skip-the-line tickets with GetYourGuide, or Viator.

Internet: Get connected wherever you go with Airalo.

Discover More Ancient Routes

Adventures in Sri Lanka - The Ancient Ceylon

Discover Portugal, Madeira & Azores

Explore Ecuador & The Galapagos

Hiking in Switzerland & Italy

ABOUT ME

I’m João Petersen, an explorer at heart, travel leader, and the creator of The Portuguese Traveler. Adventure tourism has always been my passion, and my goal is to turn my blog into a go-to resource for outdoor enthusiasts. Over the past few years, I’ve dedicated myself to exploring remote destinations, breathtaking landscapes, and fascinating cultures, sharing my experiences through a mix of storytelling and photography.

SUBSCRIBE

Don’t Miss Out! Be the first to know when I share new adventures—sign up for The Portuguese Traveler newsletter!

MEMBER OF

RECENT POSTS

COMMUNITY

TRAVEL INSURANCE

Lost luggage, missed flights, or medical emergencies – can you afford the risk? For peace of mind, I always trust Heymondo Travel Insurance.

Get 5% off your insurance with my link!

2 thoughts on “The Route of: Nellie Bly”

OMG!!! This article perfectly captures all of the things I love about Nellie Bly. She is an icon and I wish more people would learn about her. I think she would have enjoyed the journey less if she had taken a plane, so I am glad they were not invented yet. I would 100% take the trip she did, although it definitely would cost more now.

Hey Zoe! I’m delighted to see people enjoying my “Routes” section on the blog, especially Nelly Bly’s. She was a pioneer and indeed a rarity for her time. And you are right, it would no doubt cost more than it cost her since she was sponsored by a Newspaper ahah. But if you’d take a plane with so many low-cost companies nowadays you’d possibly make it cheaper. Give it a try! All the best, João